[latexpage]

Recently, I was working on a project and stumbled upon a fun little puzzle I needed to solve for it. Incidentally, this is why I love research and problem solving more generally! There's a naive solution, a somewhat clever solution, and maybe even a very clever solution (but you'll need to supply that one :P).

Here's what I needed. For a given $N$, I want to produce (a list of) all tuples of length $N$, where every element is one of (-1, 0, 1). That would be trivial, but there are a few more constraints:

- The order matters ((1, 0, 1) isn't the same as (0, 1, 1)),

- The tuples have to be unique (i.e., no tuple is repeated), and

- They have to be sorted by their $L^1$ norm (in increasing order).

I only mention (2) because some combinatorial methods will end up giving you repeats of the same tuple like (1, 1, 0), where it produces that tuple twice because it treats the two 1's as separate elements. Let's assume that you're processing each produced tuple, don't want to waste time processing repeats, and don't want to waste time doing something like putting seen tuples into a set and then checking each new one to see if it's in the set. You just want a nice stream of unique tuples.

(3) is what makes this problem hard. In case you're not familiar, the $L^1$ norm is the sum of the absolute values of a vector. For example, for an array x, in python it would be np.sum(np.abs(x)). So the $L^1$ norm of (1, 1, -1, 0, 1) would be 4. For ties between tuples of the same norm, we don't care about the order. I.e., (1, -1, 0) and (-1, 0, -1) both have $L^1$ norm 2, so it doesn't matter which gets produced first.

Lastly, it's not quite a constraint, but let's assume that we only actually want the first $M$ of these tuples in the sorted order. So we don't need all of them, but assume that $M$ is ~10,000.

So there are obviously lots of ways to go about this! The most naive is to produce every tuple, put them in a list, and then sort that list by the $L^1$ norm. To produce the list, I'm using the infinitely-useful itertools. This looks like:

import numpy as np

import itertools

N = 2

iter = itertools.product([-1,0,1], repeat=N)

iter_list = []

i = 0

while True:

try:

x = next(iter)

iter_list.append(x)

i += 1

print(x)

except:

print(f'\n\nDone in step {i}!')

break

iter_sorted = sorted(iter_list, key=lambda x: np.sum(np.abs(x)))

print('\nSorted:\n')

[print(x) for x in iter_sorted]

and produces:

(-1, -1) (-1, 0) (-1, 1) (0, -1) (0, 0) (0, 1) (1, -1) (1, 0) (1, 1) Done in step 9! Sorted: (0, 0) (-1, 0) (0, -1) (0, 1) (1, 0) (-1, -1) (-1, 1) (1, -1) (1, 1)

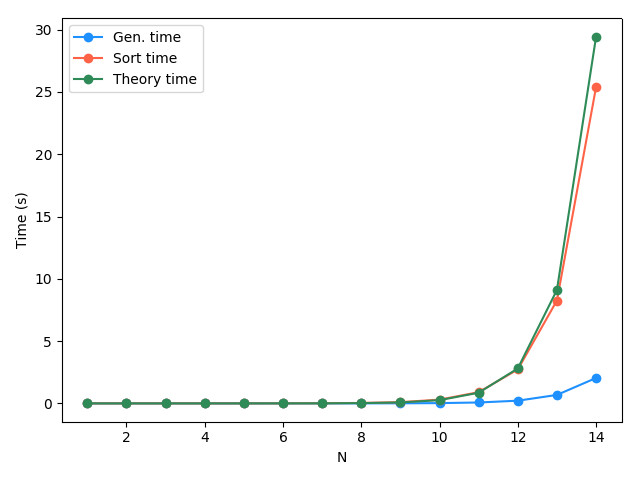

So, that works, but has two major problems. There are 3 options for each element tuple, so for a length of $N$, there are $3^N$ unique tuples. That might not be a big deal for $N = 12$ (~500,000), but it's gonna get nasty quickly. As an example, I ran the above code and measured the runtime of the list generation part as well as the sorting runtime:

You can see that the generation time is probably negligible, but the sort time explodes. I also plotted the "theory time", which was my guess for what it would take. Since a decent sorting algorithm goes as $O(K) \sim K \textrm{log}(K)$ ("big K notation" :P) for a list of length $K$, and for us $N$ is actually the length of the tuples to produce, our list size is $K = 3^N$ and the sorting should take $(3^N) \textrm{log}(3^N)$. That's what I plotted and I was surprised to find it actually match so well! It clearly needed to be scaled, so I just kind of eyeballed it and found a constant factor of 4 worked well.

(You can see that it's actually a little different. I'm guessing some clever internal python optimization stuff makes it a little faster than $O(K) \sim K \textrm{log}(K)$, like $O(K) \sim 0.9 K \textrm{log}(K)$ or something. Another aspect is that as $N$ gets bigger, maybe the key=lambda x: np.sum(np.abs(x)) isn't negligible, or something.)

Anyway, so $N = 14$ is about as high as I had the patience to wait for, and $3^{40}$ is the comically absurd 12157665459056928801. And, aside from time issue, if you do it by sorting a list, you also have to store that list in memory!

Clearly, there's gotta be a better way. What's your best guess? I'll add a spacer here in case you want to try :)

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

My first lead was that, like above, because sorting a large list means keeping it in memory, I knew that it had to be generated dynamically, already sorted. This points to using python generators, which are magic if used properly. My second hunch was that it would involve using the combinatoric itertools, because they're a pretty great way to produce generators of various kinds of sequences from a small set. The trick is figuring out how to use them here with the constraints above.

I'm guessing there are lots of ways, but here's how I did it. I'm gonna use the word "sparsity" here to mean "how low the $L^1$ norm is". So the goal here is to produce all the tuples in order of decreasing sparsity. It seemed like the problem could probably be broken down into two parts: (1) for a given sparsity, like $L^1 = 4$, produce all the tuples with that sparsity, and (2) repeat that, but for decreasing levels of sparsity, starting at $L^1 = 0$.

In this problem, a sparsity of $L^1 = R$ means that there are $R$ nonzero elements. One way to get the set of tuples with this sparsity is by first choosing one set of the values those $R$ elements could take, and then selecting each of the positions those $R$ nonzero elements could take. For example, for $R = 2$, the only sets the nonzero values can take are [(-1, -1), (-1, 1), (1, -1), and (1, 1)]. So for $N = 5$, you just need to specify all the combinations of indices of a 5-tuple (with all elements otherwise 0) that they could be assigned to. Note that it's combinations you need to get, because for values (1, 1), indices (2, 4) and (4, 2) would give you the same resulting 5-tuple of (0, 0, 1, 0, 1) (0 indexed).

So the pseudocode could be:

For R = 0, ..., N:

For V_nonzero = next tuple of R nonzero elements

For I_nonzero = next tuple of R unique, ordered indices between 0 and (N - 1)

A = array of N zeroes

Assign each A[I_nonzero_i] = V_nonzero_i

There are two missing details still. The first is simple: which itertools to use? For the first one, itertools.product([-1, 1], repeat=R) will give you the $2^R$ combinations of $R$-tuples formed by all choices of [-1, 1]. For the indices, itertools.combinations(range(N), R) will give you all the combinations of $R$ indices between 0 and $N - 1$, so it won't give you (1, 3) and (3, 1), for example.

The second detail is how to actually do the vague lines like "For $V_{nonzero}$ = next tuple of..." in the pseudocode above. Again, maybe lots of ways, but I found recursion to actually be easy here. When it's gone through all the tuples of the generator of the inner loop (the indices tuples), it has to "tick over" to the next set of values, by calling next() on the values generator. Likewise, when it has gone through all the unique sets of $R$ nonzero values, it has to increase $R$ and start over again!

I think it's best explained in code at this point!

import numpy as np

import itertools

class IterComb:

def __init__(self, N):

self.N = N

self.N_nonzero = 0

self.nonzero_gen = itertools.product([-1,1], repeat=self.N_nonzero)

self.nonzero_tuple = next(self.nonzero_gen)

self.nonzero_ind_gen = itertools.combinations(range(self.N), self.N_nonzero)

print(f'\t==>3^{self.N} = {3**self.N} total tuples.')

def get_next_list(self):

try:

nonzero_ind_tuple = next(self.nonzero_ind_gen)

arr = np.zeros(self.N)

for val,ind in zip(self.nonzero_tuple, nonzero_ind_tuple):

arr[ind] = val

return arr

except StopIteration:

try:

self.nonzero_tuple = next(self.nonzero_gen)

self.nonzero_ind_gen = itertools.combinations(range(self.N), self.N_nonzero)

return self.get_next_list()

except StopIteration:

if self.N_nonzero < self.N:

self.N_nonzero += 1

self.nonzero_gen = itertools.product([-1,1], repeat=self.N_nonzero)

return self.get_next_list()

else:

print('Generators finished!')

return None

iter = IterComb(3)

i = 0

while True:

x = iter.get_next_list()

if x is not None:

i += 1

print(x)

else:

print(f'\nDone in step {i}!')

break

Which produces...

==>3^3 = 27 total tuples. [0. 0. 0.] [-1. 0. 0.] [ 0. -1. 0.] [ 0. 0. -1.] [1. 0. 0.] [0. 1. 0.] [0. 0. 1.] [-1. -1. 0.] [-1. 0. -1.] [ 0. -1. -1.] [-1. 1. 0.] [-1. 0. 1.] [ 0. -1. 1.] [ 1. -1. 0.] [ 1. 0. -1.] [ 0. 1. -1.] [1. 1. 0.] [1. 0. 1.] [0. 1. 1.] [-1. -1. -1.] [-1. -1. 1.] [-1. 1. -1.] [-1. 1. 1.] [ 1. -1. -1.] [ 1. -1. 1.] [ 1. 1. -1.] [1. 1. 1.] Generators finished! Done in step 27!

Neato!

Running this for $N = 100$ and getting the first 50,000...

==>3^100 = 515377520732011331036461129765621272702107522001 total tuples. i = 50001, breaking Took 0.074 s!

Yeah, that's a little better.

So that was my solution. However, I bet there are many others. This one does the job, but it's also a little complicated, and relies on itertools, which is awesome, but it'd be nice to have one that's so simple I don't need it.

One idea I was considering is expressing decimal numbers from 0 to $3^N$ in base 3, in which each digit would have values in [0, 1, 2]. That's (for our purposes) the same as [-1, 0, 1], or another mapping (switching up the order if it's more convenient). From my experience in binary, there's probably some clever method to iterate through these, but I haven't thought about it enough yet.

Let me know if you have a better solution!