[latexpage]

Let's start with a fun gif!

Something I've been thinking about recently is neuroevolution (NE). NE is changing aspects of a neural network (NN) using principles from evolutionary algorithms (EA), in which you try to find the best NN for a given problem by trying different solutions ("individuals") and changing them slightly (and sometimes combining them), and taking the ones that have better scores.

For example, a really simple NE algorithm could be where the number of nodes of the NN are set, as well as the connections between them, but each individual has a different set of values for the weights of those connections. When you "mutate" an NN, you change one or several of those weights. The fitness function (FF) could be the score in a game played by that NN (so, you'd have to at least match the number of inputs and outputs for the game). So you have a generation of N individuals play the game, then choose the ones that scored best, and change them slightly or recombine them to get the next generation.

Something that attracts me to NE is that it's similar to how our brains developed (being very liberal with some definitions, anyway). Our brains didn't get to the crazy complex things they are by gradient descent, they developed via the species randomly "trying" things and "keeping" the ones that worked. On the flip side, it understandably might sound crazy to be (semi) randomly searching for NN weights when we have pretty great methods for finding them.

You can't read the literature on NE for too long without bumping into NeuroEvolution of Augmenting Topologies, or NEAT. While the example I gave above is the simplest way you could do NE, Kenneth Stanley proposed another thing you can mutate: the number of nodes, as well as the connections between them! (The paper actually does a bunch more, but that simple version is what I'll do.)

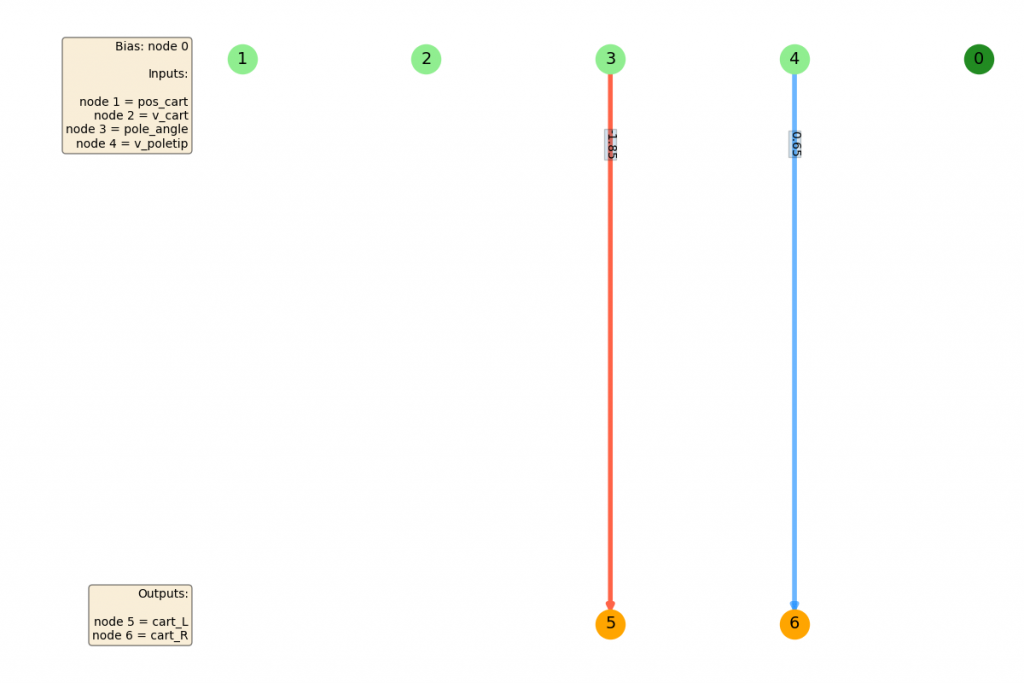

So, you could start out with a NN like this:

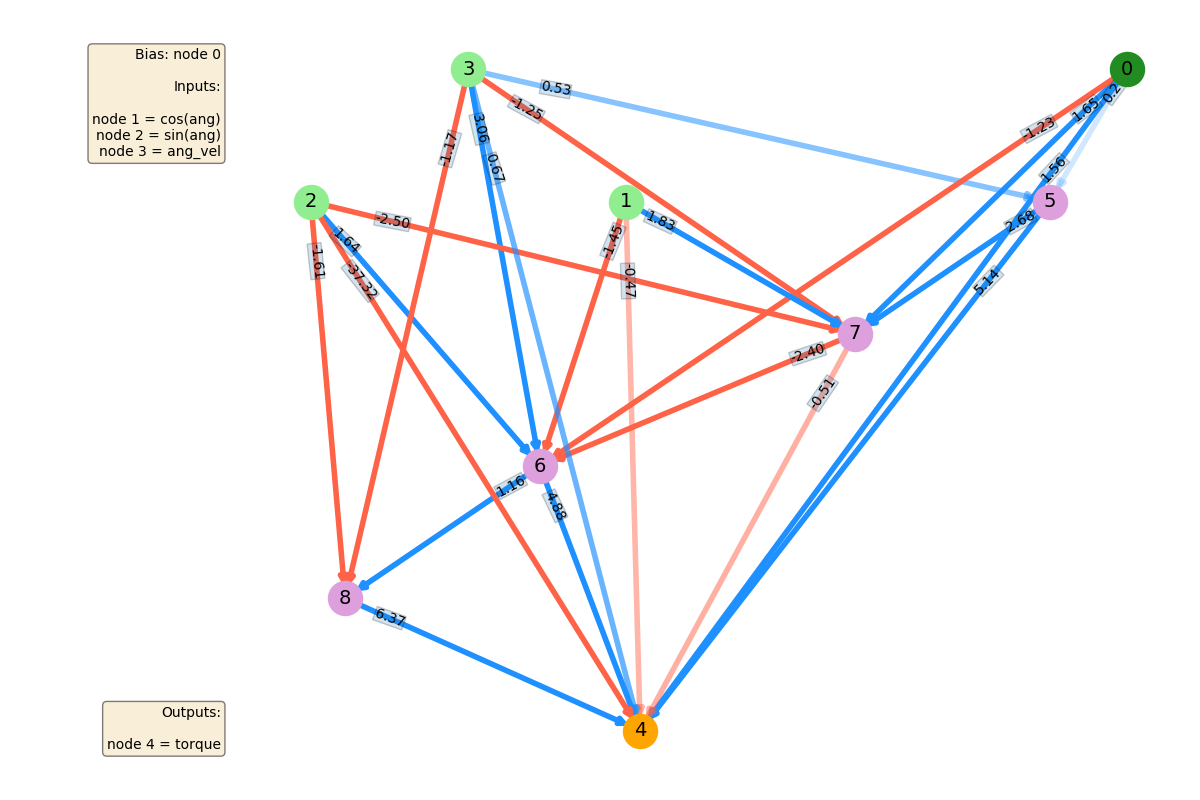

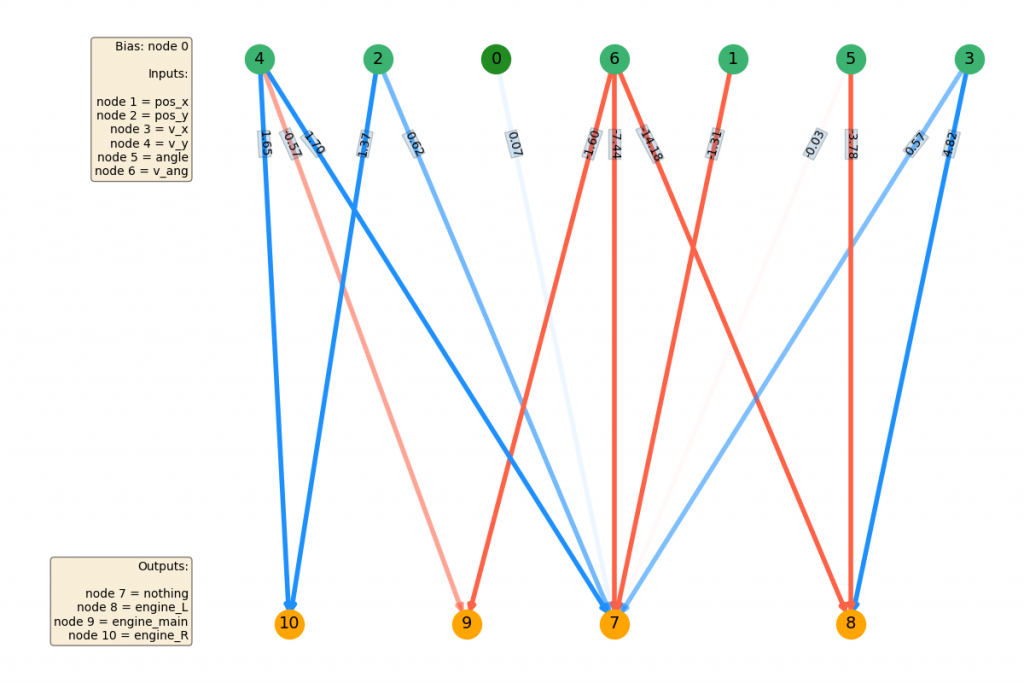

...and end up with one like this after evolving for a while:

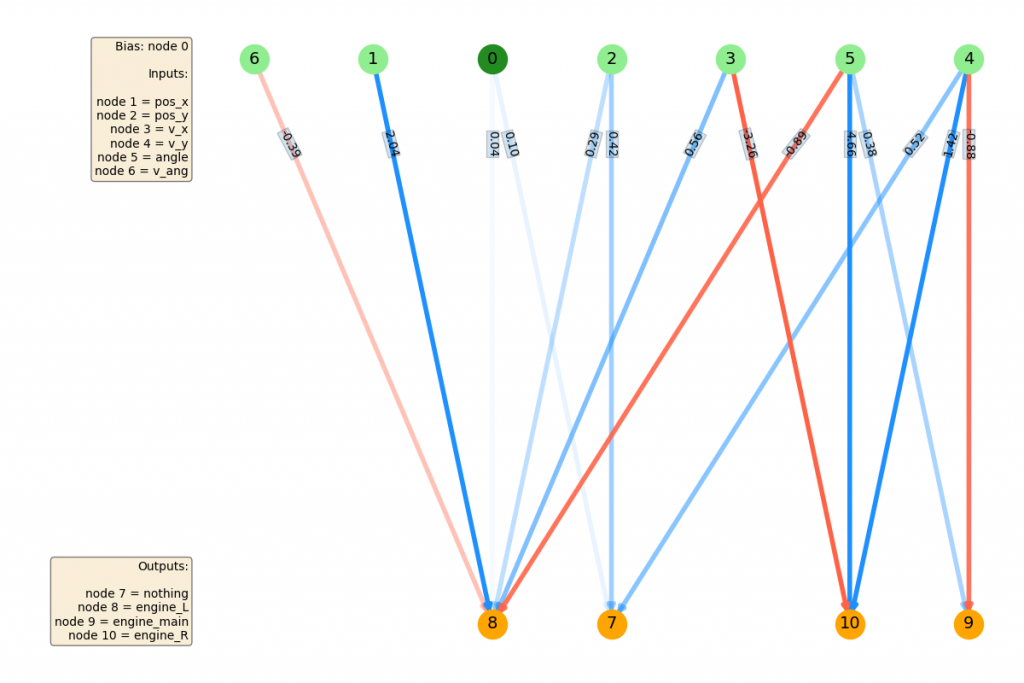

I used networkx for this plot, and made it so the connection weights are blue for positive values and red for negative, with both being more opaque, the bigger the magnitude. I've also labeled the input nodes in light green, the output nodes in orange, the bias node in dark green, other nodes in lavender (if there are any), and put a legend for each of their corresponding meanings.

If you wanna be cynical, you could ask how much this is really an improvement over just choosing a NN with conservatively many enough nodes/connections to begin with and then doing the first method I mentioned above (often called "fixed topology"). Here are a few answers to that, off the top of my head. First, if done right, this potentially lets you find the absolute simplest NN that can solve your problem. Another is that it can create unusual topologies of NN's -- for example, even restricting them to strictly feedforward, non recurrent NN's, it can essentially create "skip" connections (and layers basically aren't defined at all). There are more interesting and powerful advantages, but I'll leave it at that for now.

Interestingly, KS actually did a paper on this with Uber AI in the past few months! They use NE to play the same Atari games from the famous Deepmind DQN paper. They actually do better than DQN on a few examples, and supposedly with way less training time! Some reviewers of it seemed a bit skeptical of some of the bigger claims (not comparing it to the best DQN techniques, if I recall), but either way, it's pretty cool to see EA doing something competitive.

So, I wanted to dip my toe into the NEAT water. Instead of creating my own environment for once, I decided to try that "being efficient" thing and use OpenAI gym, which was really simple to set up and use. Here's what I do. All individuals start with the same topology: 1 bias node, that always has a value of 1.0, $N_{in}$ input nodes (dependent on the environment), and $N_{out}$ output nodes (same). They start with no connections between them, so they're going to be horrible at first.

The network is basically an RL-style Q-network, where at each iteration, the state is given as input, and the output nodes give Q values for each of the actions, which I select with argmax (I think I could just as effectively do a policy network instead just as easily, and do a softmax over the outputs to select them, since I'm not really using any RL theory, just a common structure for the function approximation). However, I want to emphasize that this is not using any RL algorithm. I'm just choosing the action to take from the NN in the same style as you might with Q-learning.

Every generation, each of the $N_{pop}$ individuals play the gym game, and get a FF score. They're then sorted by this, and the top $N_{best}$ are chosen and duplicated as many times as needed to get $N_{pop}$ again. Then they're each mutated. I also do a thing I've seen in lots of papers, where the "champion" (best) is passed to the next generation without mutation.

Mutation can do three things: 1) change a weight, with probability 0.98, by a Gaussian random with SD = 1.0, 2) add a weight between two nodes, with probability 0.09, 3) remove a weight between two nodes with probability 0.05, or 4) add a node between two existing nodes, with probability 0.0005. I just grabbed these percentages from some NE paper, but their relative values make some intuitive sense: for many problems, if a NN has enough nodes and connections, the main problem is probably that its existing weights are bad, so most mutations should change that.

I'm actually not doing mating here, since I think mating is potentially really complicated, I see lots of papers not doing it either, and I think I can get what I want from just mutation anyway.

So let's try it!

The first environment I tried was CartPole, the classic. The goal is to keep the pole upright by moving the cart to the left or right. The action space here is discrete, so you only choose one action each timestep and that action is done some constant amount. The episode ends if the cart goes off the screen or the pole deviates from the vertical too much.

Here are 9 consecutive runs with the best agent, from a population of 16, 256 generations, 2 runs with each agent (~5 min runtime on my derpy laptop):

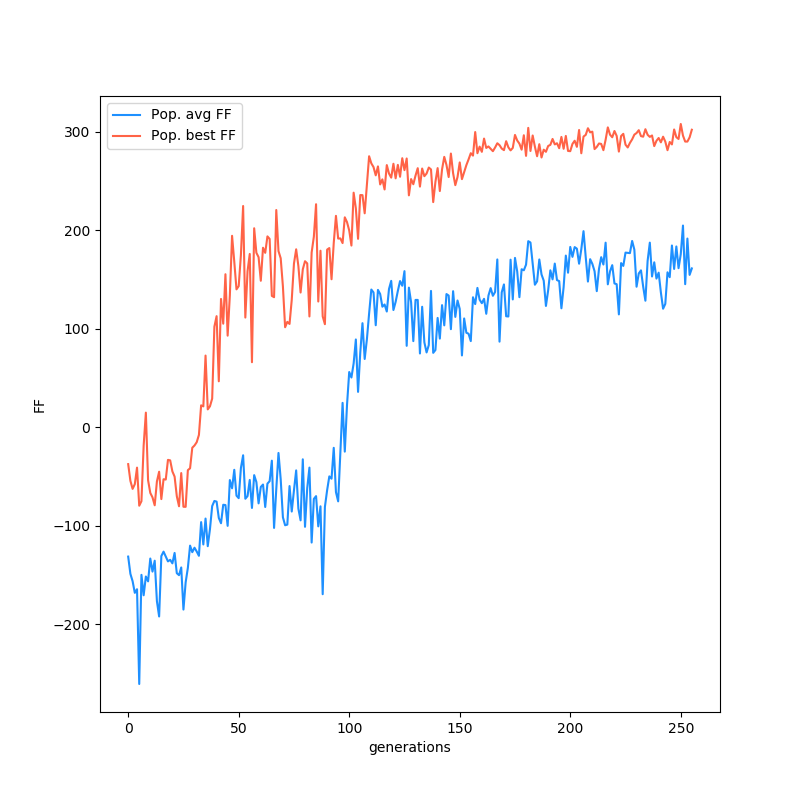

Here's a plot of the FF of the best individual at each generation, as well as the mean of the population:

Finally, here's the best NN that it produced.

CartPole gets solved pretty quickly, since it apparently needs an incredibly simple NN to work. This makes sense. The position of the cart isn't important at all really (even if you're near the edge, if you have to go off screen to keep the pole up, you're just in between a rock and a hard place). The cart velocity doesn't matter a ton either. Pretty much the only things that would determine your choice are the pole angle, and to a lesser extent, the angular velocity of the pole. You can see that the bias doesn't need to be connected at all for this one.

The next environment I experimented with was Lunar Lander. The reward structure is a bit weird, but the main idea is that you're trying to land the spaceship within the flagged area, upright, and softly, or the lander will explode and you'll get punished. The state space has 6 dimensions: the x and y positions, the x and y velocities, the angle of the spaceship, and the angular velocity of it. There are 4 discrete actions: main thruster (out the bottom), left and right thrusters, and do nothing.

Here are 9 consecutive runs with the best agent at the end, from a population of 64, 256 generations, 2 runs with each agent (~2 hrs runtime on my derpy laptop):

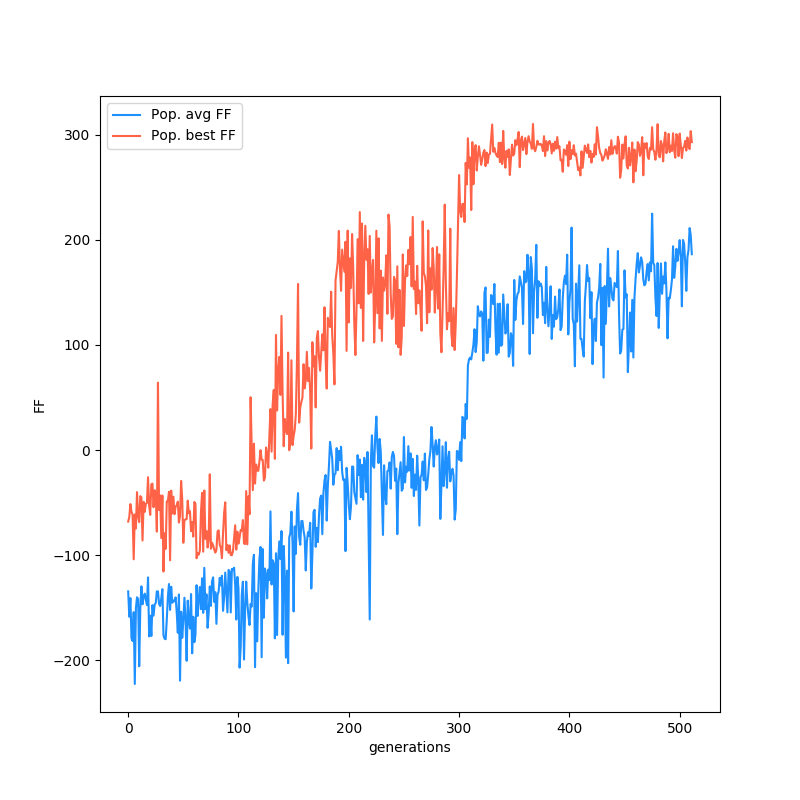

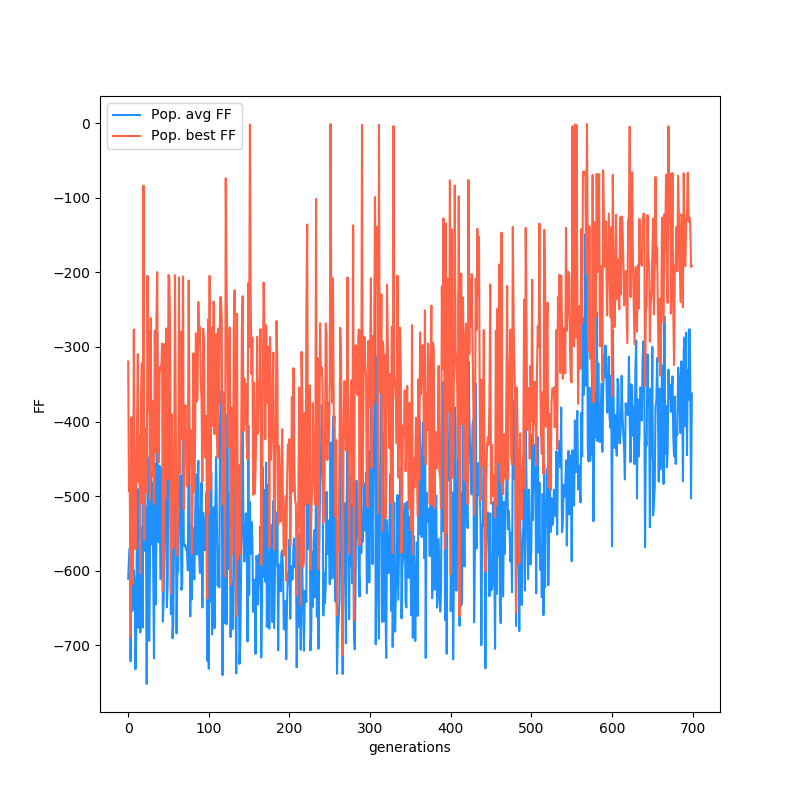

Here's a plot of the FF of the best individual at each generation, as well as the mean of the population:

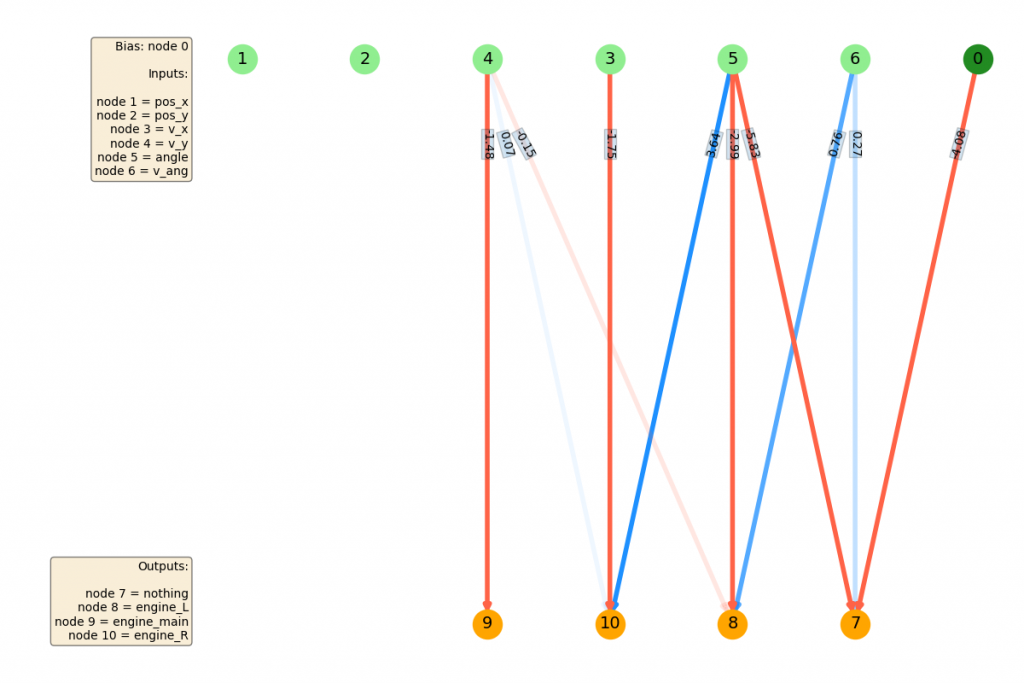

Finally, here's the best NN that it produced. Before I saw the results, I completely predicted that the EA would need to create at least a hidden layer. From the toy problems I had done before, it seemed like pretty simple problems still need the ability to create functions that need at least one nonlinearity. But...

It's actually still totally linear! Apparently you can get pretty good behavior with just the right combo of weights.

There were a few little tricks I had to figure out. One is that it seems very critical to have each individual do more than one run (game) in a generation, to get the FF. LL has some randomness to it, so every game is a little different. If you only do one run per agent, what typically happens is that one (or a few) of the population will happen to start in a lucky position for its weights, and will get a relatively good score in that generation. However, the weights weren't actually good -- for example, maybe they make it always go left, and it got lucky and started in a position off to the right. What we really want, of course, are weights that actually do some sort of comparison/calculation of the current position and velocities, so it can win no matter where it starts. So what seems to happen when only doing one trial per agent is that any individual that might actually have a shot at getting the right weights (but doesn't have them tuned well yet) will get beaten in a given generation by one of the fluctuations, which will rise to the top and fill the population.

So, using even 2 or 3 trials per agent in each generation, and taking the mean FF of those trials, really selects for ones that can do slightly better more than once in a row. Simply, it's searches for some generalizability. You're obviously doing $N_{trials per agent}$ more runs, but it seems to be vastly more effective that doing that many more times generations.

Here's a neat thing. I was curious about whether I could see distinct and sensible changes to the NN that caused the FF to increase, so I took the plots of the current best NN over time and looked at them at a few points in the evolution. Here's the consecutive runs at the end with the best agent (for funs) and the FF plot (best and mean, but best is more meaningful here):

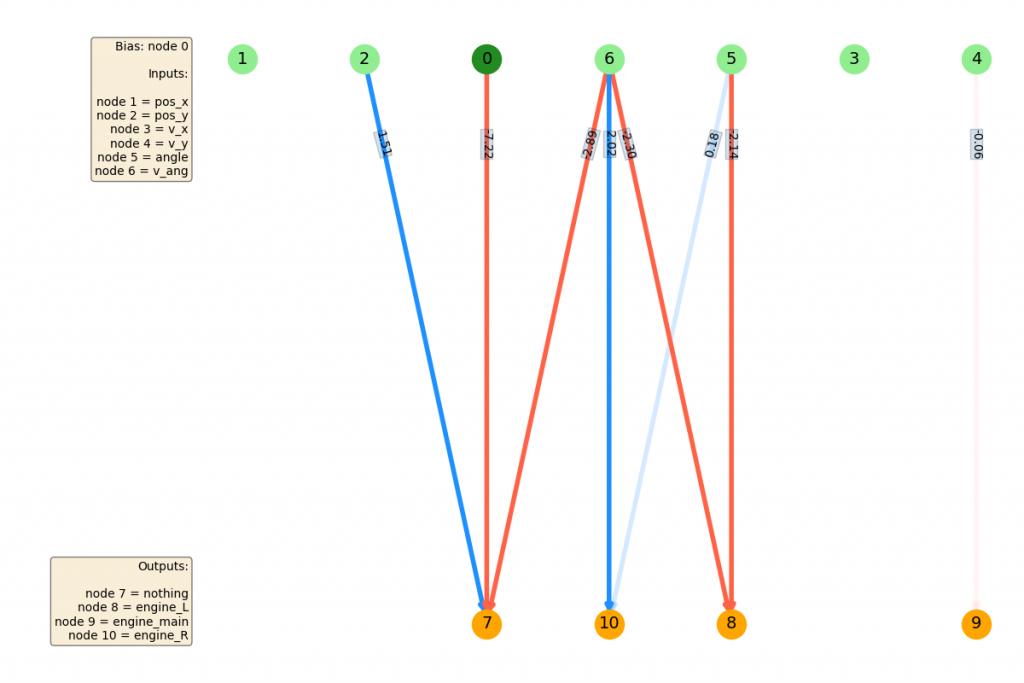

The first increase in the FF you can see starts around generation 100. If we look at the NN before...

...and after...

we can see that the main change is that node 4 ($v_y$) has now been connected (with a meaningful weight) to node 9, which controls the main thruster! This is what allows it to actually slow its descent, which is probably the most important thing for solving this problem; it seems like most instances of LL start with it right above the goal, so that control alone would be good enough for most anyway.

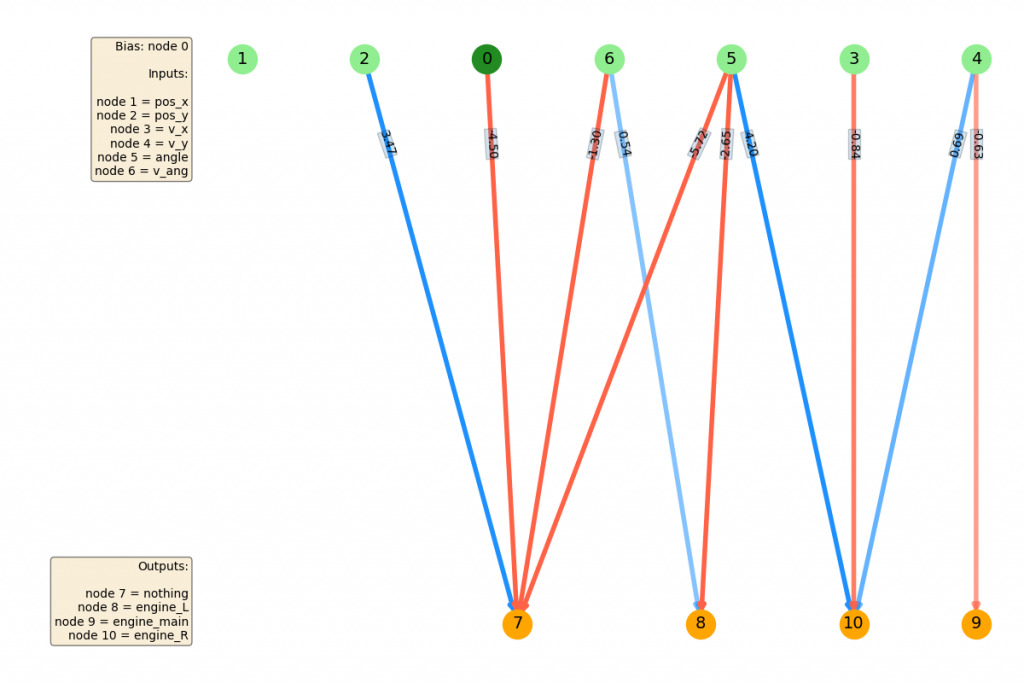

The next big jump you can see in the best FF curve is around generation 300. Again, if you look at the NN before..

...and after...

you can see that connecting node 1 ($p_x$) to one of the L/R outputs (node 8) gave it the ability to move left and right! This seems to be the big thing it was missing. After that, there are improvements, but they seem mostly incremental (maybe fine tuning weights, or using less important inputs like the angle).

The trickiest, though, was Pendulum-v0, the classic inverted pendulum. It actually only has 4 inputs and a single output, but the action space is continuous rather than discrete, meaning that we have to give it a value between -2 and 2 (no argmax is done to the output here). This corresponds to how much torque it applies to the pendulum, and you can imagine that it might be harder to evolve to because it might require the weights to be much more finely matched to each other than for the discrete case (where there's probably a lot of leeway because for the right action, you just need one sum to be bigger than another, which could be a huge margin).

Another aspect that makes it a little trickier than, say, LunarLander, is that two of the state variables need to be "coupled" for maximum effect. For example, it can't just use which side the pendulum is currently on to determine the action, because if it's, say, on the left side but not very high up, it can't just turn CW to get up, it has to swing back and forth several times to gain momentum. And, to know which direction it should be applying the torque to do this, it needs to know the current angular velocity (just like Mountain Car!).

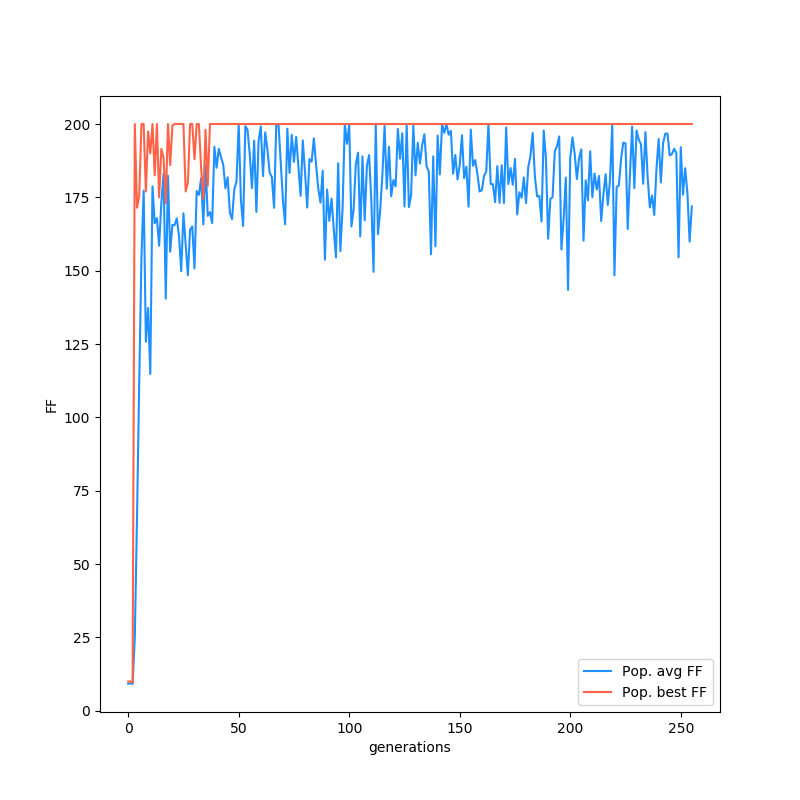

Anyway, here are some results:

Neat! You can see that this is the first one that actually requires a hidden node. Even cooler, it seems like it also skips it? I'm not sure if that's necessary, but it seems to consistently add that same node and the "skip" connections between different runs.

I also tried a little variant. Whereas CartPole and LL didn't need any extra nodes, I knew that this problem required one but I guess I hadn't appreciated how small a chance the 0.0005 probability of doing an "add node" mutation was. To see if that's what was causing it to take so long, I upped the node add mutation chance up to 0.005, and...

Haha holy hell! What a hairball. However, if we look at its actual performance:

dang! So it may be crazy overengineering it, but it at least does the job well. In fact, if you look at the first pendulum gif, you can see that even though they're standing at the end, they're all kind of leaning, because it's slightly off the vertical, so they're applying a constant force. This is actually a suboptimal solution to pendulum, because it rewards it based on both the angle (foremost I think), but also how much torque it has to exert! So this one is a better solution because it makes them end upright, where it has to exert very little force to keep them that way.

That's all for today! I'd really like to use these ideas in a more powerful and scalable way, which I'll post in the future. There are some other things I'd like to check out, but they're fairly incremental. For example, I didn't have a good intuitive guess for this: what would you guess is the best top percent to take of the generation, to mutate and create the next generation from? The reason you'd want to take a smaller percent (i.e., take the top 3% of the population and create the next generation just by mutating copies of them) is that you're choosing individuals that got a higher FF. However, you're also choosing a narrower search space: if those ones were just the best because they were lucky (or everything is noisy anyway), then that could definitely slow things down.

The code is here, but messy at the moment.

I'd also like to take a look at some form of regularization. Currently, this strategy has ways of adding and removing weights, but only adding nodes. So, over time (as seen in the pumped up version), the number of nodes can really only increase. Ideally, at some point, if the population was really good, adding a node would only hurt the behavior, so it would never add a new one. However, it seems like in practice it's pretty easy to add nodes that aren't essential, but also don't hurt behavior much, which can lead to a massive NN. So I'd like to try something with removing nodes, either by adding a cost term for the number of nodes, or by ablation, removing ones and seeing how far you can go without hurting performance.

See ya next time!