Last time, in case you missed it, I left off with a laundry list of things I wanted to expand on with Genetic Algorithms (GA). Let's see which of those I can do this time!

This is pretty wordy and kind of dry, since I was just messing around and figuring stuff out, but I promise the next one will have some cool visuals.

Generic population

Getting the population to work generically was actually remarkably easy! The idea here is that, since a GA (a simple one, anyway) is doing the same general stuff (mate, mutate, sort population by fitness, etc) independent of what species it's actually a population of, you should be able to create a new "species" class that has those mate/mutate/etc functions, and then just pass that to the Population class, which will handle everything. My original code wasn't actually too bad, but I had to change a couple things. One is that the mate() function was in the Population class, whereas it now needs to be in Board, so that took a slight change:

def mate(self,other_board):

newboard_1 = deepcopy(self)

newboard_2 = deepcopy(other_board)

crossover = randint(1,self.board_size-1)

temp = newboard_1.state[:crossover]

newboard_1.state[:crossover] = newboard_2.state[:crossover]

newboard_2.state[:crossover] = temp

return(newboard_1,newboard_2)

You just call it from one board, and another. They're both getting deepcopied anyway, so there's really no asymmetry.

The other part was making it so you can pass a class to Population when you create a new population, to tell it what species to make a population of. Now, I knew python has duck typing, in which you can just call someObj.myFunction() without knowing what class someObj belongs to, as long as that class has a myFunction() in it. But that still left the matter of how to actually create new objects within Population, which I didn't know how to do. If I had to do something in a pinch, I knew you could deepcopy an initial object you passed to it, or do some sort of branching where you have Population's __init__ select the right class from a constructor, but those are obviously both awful hacks, so I knew there must be an easier way.

And lawdy, python provides! You literally just pass Population the class itself (of the species you want to create):

So now you have, in Population.py:

class Population:

def __init__(self,individ_class,popsize,**kwargs):

self.individ_class = individ_class

self.popsize = popsize

self.population = [self.createNewIndivid(**kwargs) for i in range(self.popsize)]

self.sorted_population = None

def createNewIndivid(self, **kwargs):

return(self.individ_class(**kwargs))

And you just call it by:

from Board import Board from Population import Population pop1 = Population(Board,20,N=8)

Hot damn! Now I can try all sorts of new things. This makes it incredibly easy to test things like different mating methods, etc.

Double mutations

Something I speculated about last time is whether double mutations (i.e., where you randomly change two queens at the same time rather than one) could potentially give you more solutions, because it would potentially let you "hop out of" the set of solutions you've already found (that probably most of your population is centered around/related to). In analogy to real evolution, there are certain things that would definitely just be an improvement to a species, but it would involve far too many mutations to be likely to happen at this point; at some point, evolution/the species "made a choice" (I know there's no actual choosing here, but you know what I mean), and it turned out to be the suboptimal one in the long run (even if it was one of the very best in the whole parameter space).

To do this, I'm just going to create a new Board class, but call it BoardMutateMore, and change the mutate() function:

def mutate(self):

for i in range(self.mutations):

row = randint(0,self.board_size-1)

col = randint(0,self.board_size-1)

self.state[row] = col

This actually allows (for small boards anyway) the possibility for 1, 2, or 3 mutations if self.mutations was 3, for example, but that shouldn't be a huge deal. Speaking of, I'm unsure of which this will have a bigger effect on, smaller or bigger boards. The larger a percent of an individual you're mutating, the more it has a chance to "hop out", but it's also possible that small mutations and crossover are the much bigger effect at play, so ones that mutate too much will just get rejected. Alternatively, you may need to hop out a ton to create a new solution from ones you've already found.

So let's try both!

I'm gonna do this. For each, compare the normal (1 mutation) to the new (3 mutations), for a few trials each. I'll do this (1 and 3) for both small (8) and large (30) boards, to see how it scales. I'll also report the first generation a solution was found as well as the ending mean (which should be similar to reporting the number of unique solutions).

Board size = 8, mutations = 1:

Trial 1: first solution gen = 3, ending mean = 0.7

Trial 2: first solution gen = 4, ending mean = 0.75

Trial 3: first solution gen = 4, ending mean = 0.85

Board size = 8, mutations = 3:

Trial 1: first solution gen = 6, ending mean = 0.85

Trial 2: first solution gen = 8, ending mean = 0.8

Trial 3: first solution gen = 2, ending mean = 0.9

I was actually running the 30 board one for only 350 generations, but kept seeing that it was finding new solutions still at about 300, so upped it to give both a fair shake.

Board size = 30, mutations = 1:

Trial 1: first solution gen = 42, ending mean = 0.7

Trial 2: first solution gen = 90, ending mean = 0.75

Trial 3: first solution gen = 39, ending mean = 0.65

Board size = 30, mutations = 3:

Trial 1: first solution gen = 381, ending mean = 1.1

Trial 2: first solution gen = never, ending mean = 1.7

Trial 3: first solution gen = never, ending mean = 2

Oof, that's not good. So it seems like for both small and large boards, mutating more is worse. But what's strange is that, for a small board, where 3 mutations should be messing up a larger percent of the state, it actually doesn't affect it as badly as the same number of mutations on the larger board. So... mutations are worse, but if you have them, it's good to proportionally more of them? That seems weird...

Actually, here's my best guess. What I said isn't a big deal above, where my mutate function allows for the possibility of 1 to M mutations, might actually be a big deal. When you have 8 rows to mutate, it will fairly often "overlap" mutations such that it mutates the same row twice, which is really equivalent to just mutating that row once. If the assumption is that more mutations are actually bad, then this minimizes the number of them, and makes it closer to the original single mutation method that seems to work pretty well. When you have 30 rows, 3 mutations will almost never overlap, so almost every mutation step will really mutate 3 separate rows.

To fix this, I changed mutate() so it always mutates 3 different rows:

def mutate(self):

rows_mutated = []

mutations_left = self.mutations

while mutations_left>0:

row = randint(0,self.board_size-1)

col = randint(0,self.board_size-1)

if row not in rows_mutated:

self.state[row] = col

mutations_left -= 1

rows_mutated = rows_mutated + [row]

Now, it seems to give worse results for N = 8:

Board size = 8, mutations = 3:

Trial 1: first solution gen = 10, ending mean = 0.95

Trial 2: first solution gen = never, ending mean = 1

Trial 3: first solution gen = 3, ending mean = 0.85

Trial 4: first solution gen = 18, ending mean = 0.9

Trial 5: first solution gen = 10, ending mean = 0.9

Trial 6: first solution gen = 21, ending mean = 0.95

The ending means aren't too bad at a glance (though you should really scale them because the lowest you ever really see it go is ~0.6 and the absolute worst we've seen is ~2.0), but the first solution generation is pretty clearly awful, and definitely worse than the (6,8,2) set I found before "fixing" this multiple mutation function.

So, that seems to be it. Now, I probably could "cheat" and include both 1-mutations and 3-mutations, which would almost certainly be better than just 1-mutations (it will find the same ones as the 1-mutations but also occasionally better ones through the 3-mutations). The reason I say it's "cheating", though, is that up to this point I haven't really considered the runtime aspect of this -- what this would be doing is really just creating more offspring per generation. So, yeah, if you search more of the parameter space in each generation, you'll obviously get better options, but it takes longer.

Remember, the general strategy here is doing a cycle of Population -> Produce crossover/mutated offspring -> Cull to original size -> Repeat. The "production" step of this is kind of searching the parameter space (in a smart way, ideally), but if you do it too much, you basically end up just turning it into a more classical search. The beauty of GA is the culling step, which allows you to just "focus" on the good things.

So, that said, something cool to try might be measuring the success by time, rather than generation, and do a meta-algorithm, where I search the parameter space of "time spent expanding the population", to find what's the best combo. Doing both 1- and 2-mutations takes longer, but does it actually speed up the time to solution?

How bad is random index mating?

So like I briefly mentioned before, I think a big part of GA success is, when two states mate to produce offspring, the ability to take a good aspect of one state and keep it, while changing another part that might not be as good. That's why the "crossover" method we do with the boards is good: if you have part of an actual solution on one half of the board but the other half is hopeless, doing crossover might not lose that good part.

So I wanted to compare it to mating, but with a random switching. Currently, crossover chooses an index, 1-7, and then "splits" the array representing each board at that index, and rearranges them. So if it was 3, then [:3] for the two boards switch. So doing it randomly means picking some number of indices to switch (also 1-7), and then switching all of them. Here's the modified code to do that:

def mate(self,other_board):

newboard_1 = deepcopy(self)

newboard_2 = deepcopy(other_board)

#exclusive, inclusive

N_switch = randint(0,self.board_size-1)

switch_indices = sample(list(range(self.board_size)),N_switch)

for index in switch_indices:

temp = newboard_1.state[index]

newboard_1.state[index] = newboard_2.state[index]

newboard_2.state[index] = temp

return(newboard_1,newboard_2)

(We're back to 1 mutation, unless otherwise stated.)

...well, that was a surprise.

Board size 8:

Trial 1: first solution gen = 3, ending mean = 0.85

Trial 2: first solution gen = 3, ending mean = 0.85

Trial 3: first solution gen = 11, ending mean = 0.75

Trial 4: first solution gen = 3, ending mean = 0.75

Trial 5: first solution gen = 3, ending mean = 0.8

Not as good as crossover, at a glance, but really not too bad either! Let's try with size 30...

Board size 30:

Trial 1: first solution gen = 42, ending mean = 0.5

Trial 2: first solution gen = 60, ending mean = 0.55

Trial 3: first solution gen = 100, ending mean = 0.6

Trial 4: first solution gen = 40, ending mean = 0.6

Trial 5: first solution gen = 36, ending mean = 0.65

Hot damn! Clearly something interesting is happening. Comparing it to the same thing above (in the mutations section, but just the size 30, 1 mutation trials), it's doing better pretty much all around. Why is this? Is that splitting crossover actually not important?

Looking at the Russel and Norvig section on it, they actually mention this, but don't really explain it IMO:

Like stochastic beam search, genetic algorithms combine an uphill tendency with ran-

dom exploration and exchange of information among parallel search threads. The primary

advantage, if any, of genetic algorithms comes from the crossover operation. Yet it can be

shown mathematically that, if the positions of the genetic code are permuted initially in a

random order, crossover conveys no advantage. Intuitively, the advantage comes from the

ability of crossover to combine large blocks of letters that have evolved independently to per-

form useful functions, thus raising the level of granularity at which the search operates. For

example, it could be that putting the first three queens in positions 2, 4, and 6 (where they do

not attack each other) constitutes a useful block that can be combined with other blocks to

construct a solution.

The theory of genetic algorithms explains how this works using the idea of a schema,

which is a substring in which some of the positions can be left unspecified. For example,

the schema 246***** describes all 8-queens states in which the first three queens are in

positions 2, 4, and 6, respectively. Strings that match the schema (such as 24613578) are

called instances of the schema. It can be shown that if the average fitness of the instances of

a schema is above the mean, then the number of instances of the schema within the population

will grow over time. Clearly, this effect is unlikely to be significant if adjacent bits are totally

unrelated to each other, because then there will be few contiguous blocks that provide a

consistent benefit. Genetic algorithms work best when schemata correspond to meaningful

components of a solution.

So... crossover conveys no advantage if they are initialized randomly (which they are), but... schemas are the reason why crossover is good? And they do apply to this problem?

I'll have to think about this one.

Comparison to baseline

Something that seems important is how much better GA are than just random search. For the 8QP, using the "1 Q in each row" constraint to start, that leaves you with 8! possible states to search, which, really isn't that much. How long would it take to brute force it?

from Board import Board

from itertools import permutations

from time import time

board_size = 8

all_boards = list(permutations(list(range(board_size)),board_size))

test_board = Board(N=board_size)

start_time = time()

for board in all_boards:

test_board.state = list(board)

if test_board.fitnessFunction()==0:

print('solution found!')

print('took this long:',time()-start_time)

test_board.printState()

break

Well, with N=8 it produces ~40,000 boards and takes about only 0.04s. But with N=13... it nearly crashes my computer. So, that's probably actually because I'm creating a list of ~40,000*10^5 ~= 4*10^9 tuples representing board states to try, and that probably screws my RAM. But even if I did it sequentially (that is, producing just one board state tuple at a time in a big loop or something, to avoid this memory problem), it would still take at least ~10^5 times more, which would be ~4,000s.

All this is just to say that the GA is actually definitely slower than brute force for N=8, but insanely faster than it for N=30.

Unconstrained NQP

So far we've been doing the thing where, since you know a solution has to have exactly one queen in each row, you specify a board by a list of 8 values, where each list position is a row and the value in that position is the column value for the queen for that row. This is obviously smart, but is giving a big "hint" to the algorithm. What if we don't give it that hint?

Here, a board is now a 2D, NxN array. Each queen's position will be specified by a (row,column) tuple (which will be made to be unique for a board). What will mating be like? It's not immediately clear to me how you'd do the traditional crossover thing, because now it's possible for two queens to be in the same row. Since it seems like the "random queens switch" approach is actually way faster than traditional crossover (because...?), I think I'll do a similar thing. The queen positions for a board will be a list of 8 tuples. So I'll choose M (1-7) pairs to switch, then choose M indices. So I'll switch the queens in the list positions of those indices. Yeh?

Again, I did it for N=8 and N=30.

Board size 8, 500 generations:

Trial 1: first solution gen = 17, ending mean = 0.9

Trial 2: first solution gen = 21, ending mean = 0.85

Trial 3: first solution gen = 7, ending mean = 0.85

Trial 4: first solution gen = 9, ending mean = 0.75

Trial 5: first solution gen = 19, ending mean = 0.8

Somewhat worse, but nothing terrible.

Board size 30, 500 generations:

Trial 1: first solution gen = never, ending mean = 1.35

Trial 2: first solution gen = never, ending mean = 1.95

Trial 3: first solution gen = never, ending mean = 1.95

Trial 4: first solution gen = never, ending mean = 2.25

Trial 5: first solution gen = never, ending mean = 1.6

Wow, so pretty awful. Again, it seems like another case where the general smallness of N=8 hides the effect because you'll probably get lucky and get some solutions anyway. But with N=30, there are now ~900 positions that each mutation can change to, so it makes it pretty unlikely to have a mutation end up giving it what it needs.

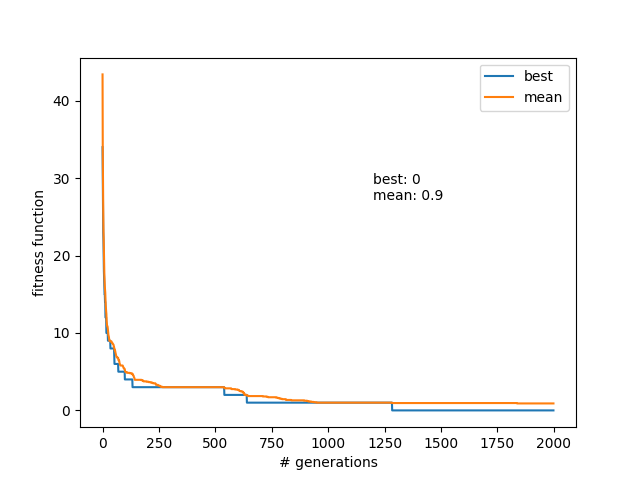

Actually, a little amendment on this. I was running it for 500 generations, because that was my baseline "long" run so far; it was usually overkill to get even N=30 in a steady state population for the past experiments. But then I realized that, if it was still often updating the mean (i.e., finding new solutions) at 400 for N=30, for this one that was effectively searching a much bigger parameter space, it would probably need far more generations to settle. So I instead did it for 2000 generations, aaaand:

Wowzers! Finding a solution in generation 1264, but I guess that's actually pretty remarkable given that each mutation has ~30*30^2 possibilities (each of the 30 queens can go to ~30^2 new spots)!

That's all for now. I have some more stuff I poked around with, so I'll probably write about that next time. For example, I've also done a comparison of GA vs Simulated Annealing, because GA is a controversial search/solving method, whereas SA is more straightforward and widely respected, I think.