My friend Mike recently showed me a puzzle game called Skyscrapers, which you can play here. It's a neat idea, in the general theme of "fill in the numbers with these constraints" puzzles like Sudoku or Verbal Arithmetic.

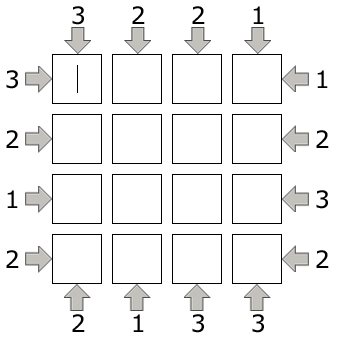

The rules are like so. You're given a board like this, representing a group of city blocks (one building per square), with numbers around the sides:

Your goal is to fill in the squares with the numbers 1 to the width of the puzzle (4 in this case), where the number represents the height of the building on that square. There can't be any repeats of numbers in a given row or column.

For each number on the side, that's the number of buildings you can see, looking down that row or column, in the direction of the arrow next to it. If there's a bigger building (number) in front of a smaller building (number) (from the viewpoint of the number on the side), you can't see the smaller building behind it. So if you were looking down a column that had [1, 2, 4, 3] in that order, you would see buildings 1, 2, 4, but the building with height 3 is hidden behind the one with height 4.

So, you can always see at least 1 (e.g., if it were [4, 2, 1, 3]), and at most 4 ([1, 2, 3, 4]). You have to place the numbers such that all the "number of buildings seen" from each side panel are satisfied, as well as the constraint I mentioned above about the numbers in each row and column all being different.

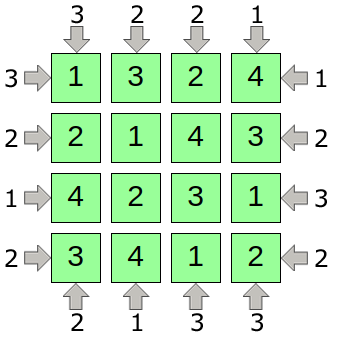

Here's that puzzle solved, to show it:

Note that for each "seen" number on a side, it's *from that viewpoint*, looking up or to the left or whatever, just to be clear.

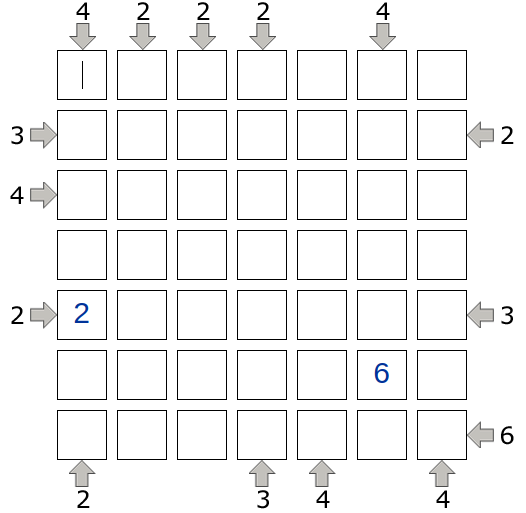

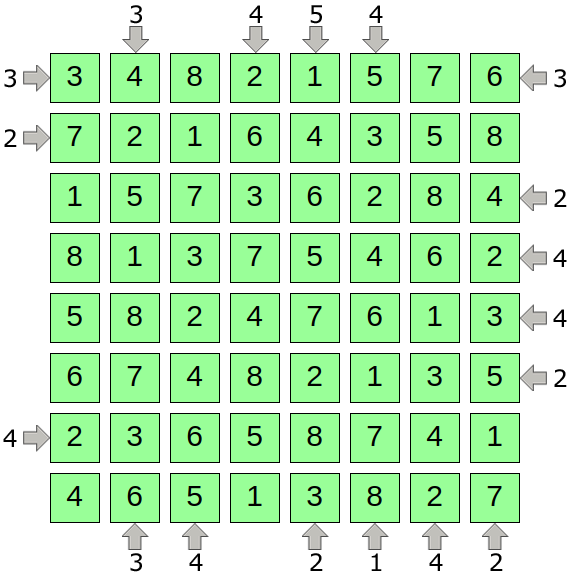

One more complication to add. There are ones of bigger sizes, like 8x8 ones, but they also make them harder by removing clues along the sides, and give you hints by adding numbers that have to be in the solution. For example:

So I wanted to solve this using techniques I've been learning. There are probably a few ways to go about it. I actually tried both Genetic Algorithms and Simulated Annealing, with varying success, but I'll save that for another post because I think they can do better that they are currently if I tweak them a bit.

This immediately appeared to me as a Constraint Satisfaction Problem (CSP), like we did in our Coursera Discrete Optimization course, which I've made a few posts about in the past. CSP are basically where you set up a set of constraints that represent the problem, such that if you find a model that satisfies all of them, you've found the solutions. The actual algorithms you use to solve these CSP are some things we used in the DO course (like branch and bound), but in practice you probably use a CP solver that someone else has already written, because it will probably do something special like look at the structure of the problem to set it up in an optimal way. If you do this, then you simply get a CP solver and set up the variables and constraints, which can actually be tricky itself.

There are many, many subtypes of CSP, and it's an insanely important, dense field (that's actually doing a lot of work behind the scenes that you might not know of). There's actually a related (/subfield?) of CP called Integer Programming (IP), where all the variables are restricted to be integers, so I guess we'll technically be doing that. To be honest, it wasn't totally clear to me what the difference was, but this and this shed a little light on the distinctions. I think we'll actually be doing CP now, because I use a few constraints like Min and Max, whereas IP only uses linear in/equalities.

We actually used Gurobi for our course, mostly because Phil knew the most about CP solvers and suggested it. It was actually really straightforward and pleasant to use in python, and we used it to solve a Vehicle Routing Problem, which is basically the Traveling Salesman Problem on crack. My only qualm was that it seemed a little annoying to install, and it's commercial, so you can either get a free license that limits the number of variables you can use, or get an academic license for free if you're part of a school.

I instead opted to use OR-Tools, Google's Optimization Tools (it's "operational research"). I did it partly because I was curious, partly because I usually like Google's style, partly because I didn't want to have to deal with the Gurobi license thing, and partly because it was super easily installed through pip3. Literally just "pip3 install ortools". I was actually flying back home from Washington state on a plane that had surprisingly fast free wifi, so I downloaded it and was off to the races.

Now, on to the problem!

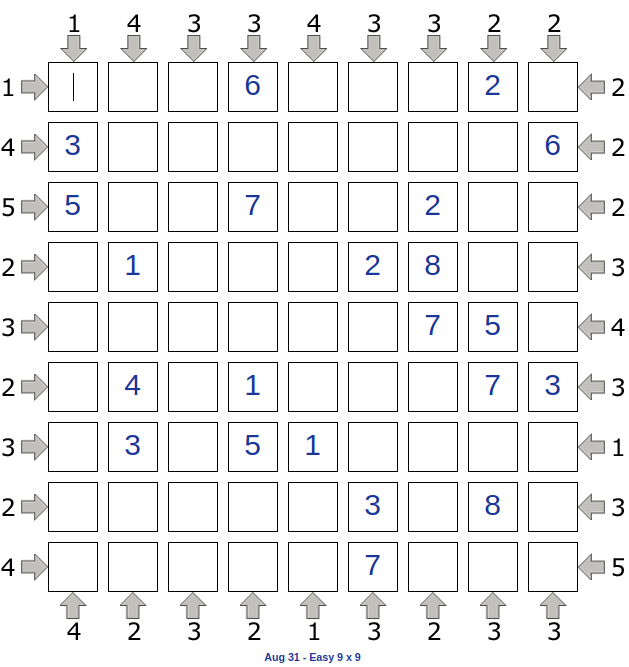

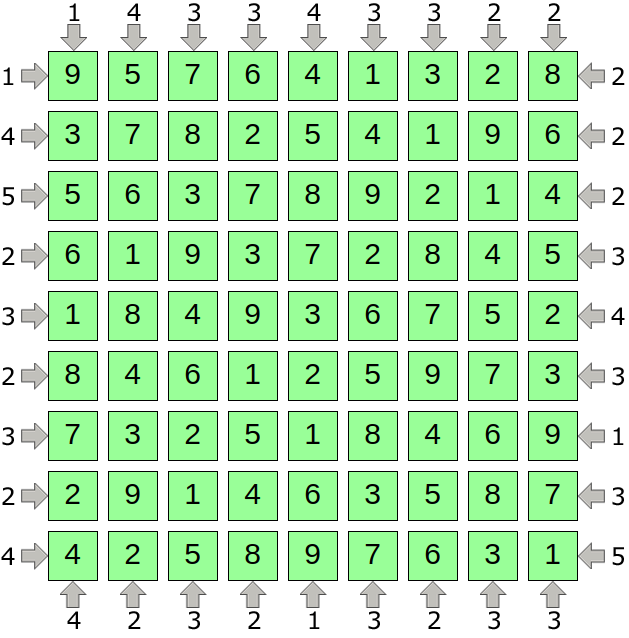

I mostly hacked around with code from the OR-tools guides they have here, since there are some details that probably don't matter immensely for my simple application. I'll go through my code bit by bit, and use this 9x9 puzzle as an example:

The first part was to actually write the puzzle in code, which is probably going to be messy no matter what. I opted to do it as a list of 4 lists, one for each side, in the order [left, right, top, bottom], where the left and right sides are read in the order top to bottom, and the top and bottom sides are both read left to right. I call this see_list, since that's what you'd see from the sides. If any aren't given (like in some puzzles), I make them a 0. I also define the list of the given numbers (if there are any) as const_list, a list of tuples, each of which is the location and value of the given number. I count down and then right, starting at index 0, for the indices, so the first const_list entry is ([1,0],3). So here's the above puzzle:

ss_99 = [[1,4,5,2,3,2,3,2,4],[2,2,2,3,4,3,1,3,5],[1,4,3,3,4,3,3,2,2],[4,2,3,2,1,3,2,3,3]] ss_99_constlist = [([0,3],6),([0,7],2),([1,0],3),([1,8],6),([2,0],5),([2,3],7), ([2,6],2),([3,1],1),([3,5],2),([3,6],8),([4,6],7),([4,7],5), ([5,1],4),([5,3],1),([5,7],7),([5,8],3),([6,1],3),([6,3],5), ([6,4],1),([7,5],3),([7,7],8),([8,5],7)] see_list = ss_99 const_list = ss_99_constlist

Next, I create the solver object and variable list:

# Creates the solver.

solver = pywrapcp.Solver("simple_example")

#Create the variables we'll solve for

ss_vars = np.array([[solver.IntVar(1, size, "a_{}{}".format(i,j)) for j in range(size)] for i in range(size)])

solver.IntVar() creates an integer that's bounded between 1 and size, inclusive, and you can give it a name. So we actually have a numpy array of these solver variable objects.

Now we have to add the constraints!

The first constraints are having all the numbers in each row and column different. I think this is the first part that makes what I'm doing CP rather than IP, because I get to use the handy AllDifferent() constraint rather than having to specify them all individually. Note that I can very handily slice the numpy array, but it has to be converted to a traditional python list before getting handed to AllDifferent(), or it whines:

#CONSTRAINTS

# All rows and columns must be different.

for i in range(len(ss_vars)):

solver.Add(solver.AllDifferent(ss_vars[i,:].tolist()))

solver.Add(solver.AllDifferent(ss_vars[:,i].tolist()))

Next, we have to add the constraints for see_list. This is the part, if any, that is a little tricky. It's pretty easy to look at the puzzle and say "yeah, you can see 3 buildings looking down that row from the right", but it's not as immediately clear (to me anyway) how you would actually take the row of numbers and extract the number of ones you can see (and then set that equal to the number you're supposed to see).

This code is pretty ugly, but I'm not sure of a cleaner way to do it. Here's what I did. I add the constraints in a loop for each entry of a side (so 1 to the size of the puzzle), and for each iteration, I first add the constraints for the left/right sides, then the top/bottom sides. I'll just show the first one for now, the constraints looking from the left, to illustrate the principle:

for entry in range(size):

#left and right

sidepair = 0

left_top = 2*sidepair

right_bot = 2*sidepair + 1

#print('adding constraint for left/right sidepair {}, entry {}: {} and {}'.format(sidepair,entry,see_list[left_top][entry],see_list[right_bot][entry]))

if see_list[left_top][entry]!=0:

solver.Add((1 + solver.Sum([solver.Min(solver.Max(ss_vars[entry,:j+1].tolist()) - solver.Max(ss_vars[entry,:j].tolist()),1) for j in range(1,size)])) == see_list[left_top][entry])

The sidepair, left_top, and right_bot things are just indices to get the relevant element of see_list. The if statement is just making sure the value isn't 0, i.e., there actually is a value we need to constrain (not a blank, like for the harder puzzles).

The instrumental part is the last line. What it's doing is the following. It's basically starting at the first element in the row (from the left in this case), and then taking two subsets of elements of the row, in order from left to right. The first subset goes from indices [1,i] and the second subset goes from [1,i+1]. The first subset represents the buildings you can see counting just the ones from 1 to i, and the second is the buildings from 1 to i+1. It takes the max of each of these (note that because we're adding a constraint, not just calculating it, we have to use the solver's Max function, not the python one). The idea here is that, as you include the "next" building (the one in the i+1 position), if the max changes, that means you could see another building (so you have to add 1 to the building count) but if it doesn't, the max was already in the range [1,i], so you don't. So we want to iterate over i such that this process will cover every subset in the row, adding 1 to the building count each time the max increases.

Because you just want a count of 1 even if the max changes by more than one (i.e., if adding the i+1 variable increased the max from 2 to 4), it seemed like I had to use something like the Heaviside step function, which I don't think is in OR-tools, but I was able to figure out a sneaky workaround. If the next building doesn't increase the max, then the difference between the maxes will be 0, which is what we want to add to the building count anyway. If the next building does increase the max, then their difference will be at least 1, if not more (but never negative, because it can only increase when we take into account more buildings). Therefore, we can take the Min (again, the solver version) of this difference and 1.

Then, we take the Sum (the fancy solver version) of these Min's, plus 1 (because you always see the fist building), and set that equal to the number of buildings we should see. Now that I look at it, you could actually just use the value at the i+1 index, not the subset, since that's the only one that matters, but you'd still need to use the subset for the [1,i] range I think. I think you could also get rid of the whole subset thing by doing it in an explicit loop for each one, keeping an updated "max seen so far" variable, but I did this and it works.

I won't go over it, but you have to do the same for see_list from the right, but you have to reverse the subsets. You also then have to change the sidepair variable so it's doing it on the top and bottom, and just slice the var matrix differently, but it's the same idea.

Lastly, we add the constraints for the given constants:

#Add constraints for given constants, if there are any

for const in const_list:

ind = const[0]

val = const[1]

solver.Add(ss_vars[ind[0],ind[1]] == val)

Now to actually solve it, we have to use a bit of ~~MaGicK!~~. We need a "collector", which basically just collects the solution. We also need a "decision builder", which we pass a few magic options. Then, we just hit Solve!

#Soluion collector

collector = solver.AllSolutionCollector()

collector.Add(ss_vars.flatten().tolist())

#The "decision builder". I just used the one from:

#https://developers.google.com/optimization/cp/cp_tasks

db = solver.Phase(ss_vars.flatten().tolist(), solver.CHOOSE_FIRST_UNBOUND, solver.ASSIGN_MIN_VALUE)

#Solve it!

time_limit_s = 1

solver.TimeLimit(1000*time_limit_s)

print('\n\nstarting solver with {}s time limit!'.format(time_limit_s))

start_time = time()

solver.Solve(db, [collector])

print('\ndone after {:.2f}s'.format(time()-start_time))

#print solutions

print('\nthis many solutions found:',collector.SolutionCount())

for sol_num in range(collector.SolutionCount()):

sol = np.array([[collector.Value(sol_num,ss_vars[i,j]) for j in range(size)] for i in range(size)])

print('\nsolution #{}:\n'.format(sol_num))

print(sol)

I added the time limit because it seems like if you give it a broken puzzle (like, you enter a wrong number), it just hangs and ctrl+c won't kill it, so you have to exit that terminal. However, the time limit doesn't seem to work. Hmmm. I also made it print out all solutions it finds (though it's usually just 1, unless you give it a really simple general puzzle).

How does it do?

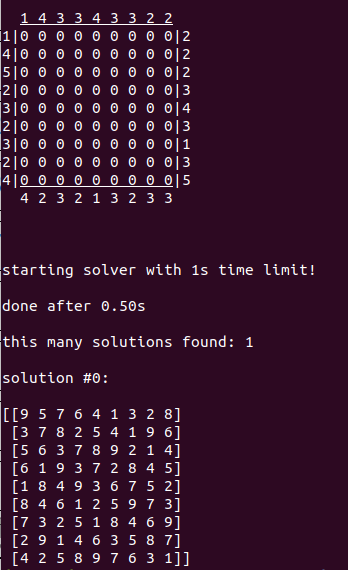

It cranks the 9x9 from above in half a second:

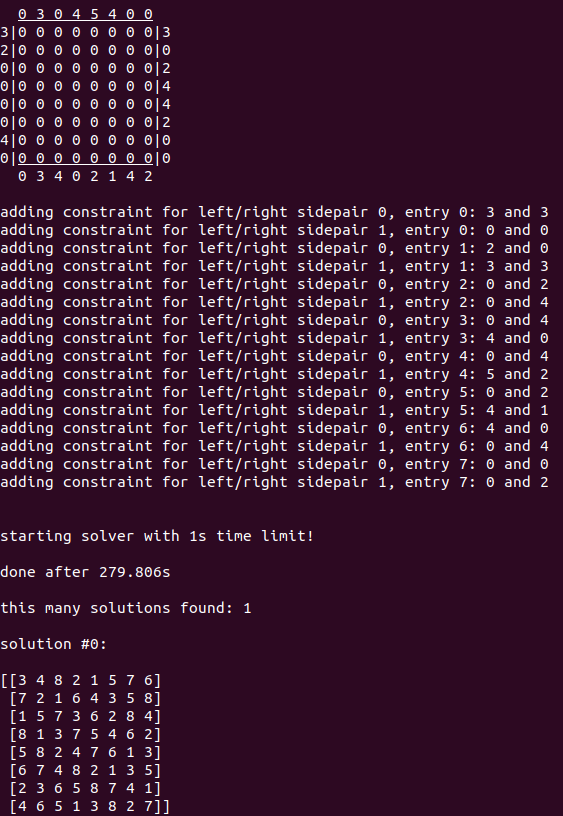

That was actually an 'easy' one though, not having any blanks. For the hardest one I can find, the 8x8 hard, it actually takes about 5 minutes of sitting there on my Asus Zenbook, but it gets it!

The website notes that larger puzzles are harder than smaller ones, such that the easy 8x8 is "far harder" than the hard 5x5, by the way.

Welp, you get the point. I'm pretty sure it'll slam anything that doesn't have too many more blanks. I'll probably make a post soon about my attempts on this puzzle through other, more handmade means, since this is honestly pretty black-box-y and feels a little like cheating (though it's a very valuable tool!). I know only the very, very basics of what CP solvers are actually doing under the hood, so it'd be cool to solve it with something where I actually know how it functions.