I first heard this puzzle when taking an algorithms class in undergrad. The prof presented it as a teaser for the type of thing you could solve using algorithmic thinking, though he never told us the answer, or what the way of thinking is. Then, it more recently came up with my friends while we were hiking, and we were talking about it. I'll talk about what I have so far, but first let's say what the puzzle actually is.

There's a building with 100 floors. You have two identical crystal eggs. They will break if dropped from (or above) some height (the same height for both), and you'd like to find that height using the fewest number of drops possible. If you drop an egg from some height and it doesn't break, you can use that egg again. Once an egg is broken (i.e., you dropped it from that breaking height or above), you can't use that egg again. So the question is, what's the best dropping strategy?

So you can use the first egg to do a faster "search" between floors 1-100 (i.e., if you drop it at floor 20 and it doesn't break, you've saved searching floors 1-20!). However, once your first egg is broken, the second egg has to be used to "scan" the remaining floors from the highest one you know it doesn't break at to the one you just broke it from. For example, if you dropped your first egg at 20 and it didn't break, and so you tried again at floor 40 and it broke, you know the breaking height is somewhere between floors [21-39], so you have to drop your second egg on floor 21, 22, 23, etc, until it breaks and you've found the floor.

So you can tell that there's a bit of a balance here between "search" and "scan". The more aggressively you search with the first egg, the more you get to skip floors when it doesn't break, but you also have to scan a larger number of floors in between when it does.

Another detail is that this problem is a little ill-posed (at least what we remember): it's unclear whether the question wants the average number of drops needed for a strategy to find the height, or maybe the least-bad worst case (i.e., if someone knew your dropping strategy and they could choose the floor to make you have to use the max number of drops) ? The average number seems better, but I think it actually ends up not mattering much (see below).

I solved this in three ways. First I did a brute search thing, which should give the actual average/worst case numbers, because it's literally trying a given strategy for the egg being on each floor, and then averaging the results. Then I do a method Phil suggested based on Dynamic Programming. Last, I do a similar thing, but with a Markov Decision Process.

Brute force

In this section, I'm going to try the brute force method. I.e., for a given drop strategy I test, I'm going to build an "ensemble" where I have it use that strategy for every possible "break floor" (the floor the eggs happen to break on). This will give me the definitive average and worst case numbers for each strategy, though it will be only "empirical"; i.e., I'll only get the best strategy for ones I try, but not necessarily the best strategy there is (see below for that!).

So I'll admit: both when I heard this problem long ago and when I heard it again here, my mind instantly went to a bisecting log type search. That means drop the first egg on floor 50. If it doesn't break, you split the difference of the remaining floors and do 75. If it doesn't break again, drop from 88 (ceil(87.5)), etc. I guess I carelessly thought that because it seems like so many CS things end up being like that, but I should've thought more!

Here's my quick and dirty code for trying the bisecting search. Excuse any messiness; I wanted to keep those comments in for diagnosing different variants I tried during this post and I'm kind of a code hoarder. The instrumental line is the curFloor = ceil((buildingHeight + curFloor)/2) one, which defines the next floor that it will be dropped from.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

from math import log,ceil,floor

minList = []

maxList = []

avgList = []

buildingHeight = 100

dropCountList = []

for breakFloor in range(1,buildingHeight+1):

firstEggWhole = True

drops = 0

lastUnbrokenFloor = 0

curFloor = floor(buildingHeight/2)

#print()

while firstEggWhole:

drops += 1

#print("drop {}: dropping from floor {}".format(drops,curFloor))

if curFloor>=breakFloor:

#print("first egg broken dropping from floor",curFloor)

firstEggWhole = False

else:

lastUnbrokenFloor = curFloor

curFloor = ceil((buildingHeight + curFloor)/2)

if curFloor==breakFloor:

#print("have to search {} more floors ({} to {})".format(((breakFloor-1) - lastUnbrokenFloor),lastUnbrokenFloor+1,(breakFloor-1)))

drops += ((breakFloor-1) - lastUnbrokenFloor)

#print("total drops:",drops)

else:

#print("have to search {} more floors ({} to {})".format((breakFloor - lastUnbrokenFloor),lastUnbrokenFloor+1,breakFloor))

drops += (breakFloor - lastUnbrokenFloor)

#print("total drops:",drops)

dropCountList.append(drops)

minDrops = min(dropCountList)

maxDrops = max(dropCountList)

avgDrops = sum(dropCountList)/len(dropCountList)

print("min: {}, max: {}, avgDrops: {}".format(minDrops,maxDrops,avgDrops))

So I calculate both the max (worst case) and avg of the ensemble of the 100 cases of when the breaking height is on each floor. I get:

min: 2, max: 50, avgDrops: 19.12

That 50 is really a killer, because for half of the ensemble (floors < 50), you lose your first egg immediately and then have to scan up to it. That's painful and probably why this method doesn't work.

Anyway, my smarter friends more immediately thought of a constant search method, where the first egg has some stride that it checks at until the egg breaks. So if you had a stride of 20, you might take the first egg and check at 20, 40, 60, etc, until it breaks, and then scan the rest. It's pretty easy to calculate the worst case for this method; it's basically setting the breaking floor to use the first egg as much as possible, and then set it again to make the second egg have to scan as much as possible. So for 20, you want to make the first egg do 20, 40, 60, 80, and break on 100, meaning it will have to use the second egg to search 81-99.

Like above, there's definitely going to be some sweet spot where the aggressiveness of the search stride isn't outweighed by the cases where you have to scan a bunch with the second egg. My friends immediately recognized that it was probably a stride of 10, and it's probably not a coincidence that 10 = sqrt(100). So I made another quick dirty little program (be merciful pls) to try a bunch of these strides and plot the avg and worst cases:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

#skipLengthList = list(range(15,70))+[100,200,300,500,800,980]

skipLengthList = list(range(1,20))+[30,40]

minList = []

maxList = []

avgList = []

buildingHeight = 1000

for skipFloorLength in skipLengthList:

dropCountList = []

#print("\nskipFloorLength =",skipFloorLength)

for breakFloor in range(1,buildingHeight+1):

firstEggWhole = True

drops = 0

lastUnbrokenFloor = 0

#skipFloorLength = 5

curFloor = skipFloorLength

#print()

while firstEggWhole:

drops += 1

#print("drop {}: dropping from floor {}".format(drops,curFloor))

if curFloor>=breakFloor:

#print("first egg broken dropping from floor",curFloor)

firstEggWhole = False

else:

lastUnbrokenFloor = curFloor

curFloor += skipFloorLength

if curFloor==breakFloor:

#print("have to search {} more floors ({} to {})".format(((breakFloor-1) - lastUnbrokenFloor),lastUnbrokenFloor+1,(breakFloor-1)))

drops += ((breakFloor-1) - lastUnbrokenFloor)

#print("total drops:",drops)

else:

#print("have to search {} more floors ({} to {})".format((breakFloor - lastUnbrokenFloor),lastUnbrokenFloor+1,breakFloor))

drops += (breakFloor - lastUnbrokenFloor)

#print("total drops:",drops)

dropCountList.append(drops)

minDrops = min(dropCountList)

maxDrops = max(dropCountList)

avgDrops = sum(dropCountList)/len(dropCountList)

#print("min: {}, max: {}, avgDrops: {}".format(minDrops,maxDrops,avgDrops))

minList.append(minDrops)

maxList.append(maxDrops)

avgList.append(avgDrops)

avgListArgMin = np.argmin(np.array(avgList))

maxListArgMin = np.argmin(np.array(maxList))

print('best skip length in terms of avg case:',skipLengthList[avgListArgMin])

print('best skip length in terms of worst case:',skipLengthList[maxListArgMin])

print('best avg case:',avgList[avgListArgMin])

print('best worst case:',maxList[maxListArgMin])

avgLine = plt.plot(skipLengthList,avgList,'bo-',label='avg')

maxLine = plt.plot(skipLengthList,maxList,'ro-',label='worst')

plt.axvline(skipLengthList[avgListArgMin], color='b', linestyle='dashed', linewidth=1)

plt.axvline(skipLengthList[maxListArgMin], color='r', linestyle='dashed', linewidth=1)

plt.xlabel('skip floors length')

plt.ylabel('# of drops')

plt.title('building height = '+str(buildingHeight))

plt.legend()

plt.show()

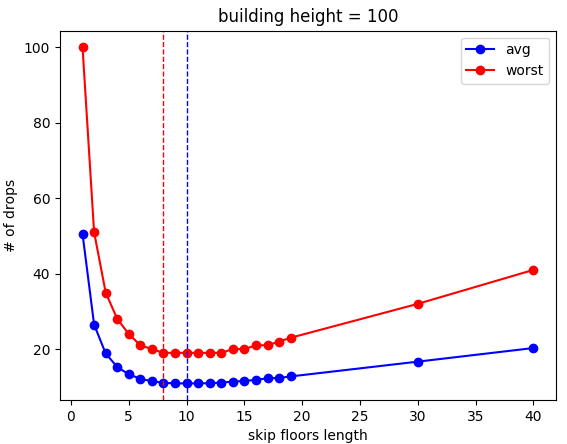

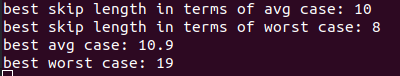

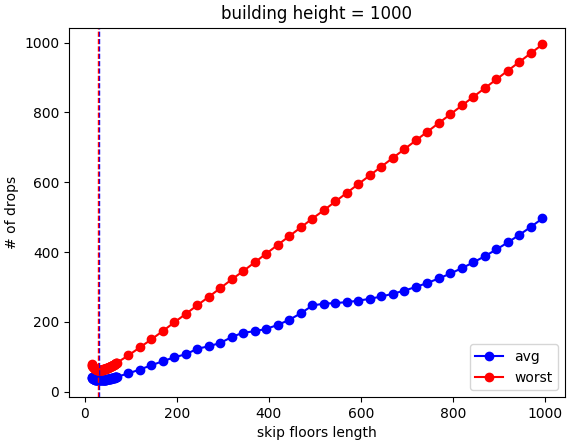

So you can see that my friends were right. The dotted lines show the positions of the best values for the two metrics (the red one is actually a plateau at that, it just selected 8 because argmin() selects the first value it finds, so ignore that). Interestingly, the best avg case is also about 10. Hmmm. You can also see that the worst case pretty much perfectly tracks the average case.

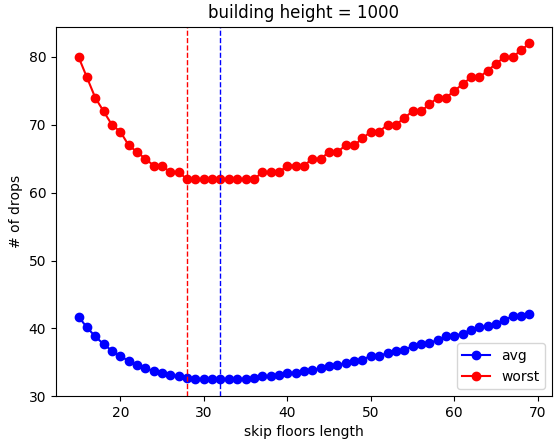

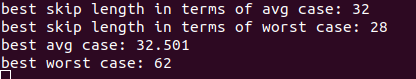

To check, I also tried it with a building size of 1000 (and therefore, a step size of floor(sqrt(1000)) = 32, which gave similar results:

Same deal. Here's a neat little detail, though. This is the very "zoomed in" set of test strides, because I guessed it would be around the sqrt(building height). If you zoom out:

In the region that's a bad strategy anyway, the worst case increases as you might expect, but you see some pretty interesting behavior of the average case, where there are different "regimes" or something. Maybe I'll investigate this more at some point, but I wonder if it's a coincidence that there's what looks like a cusp at (building height)/2...

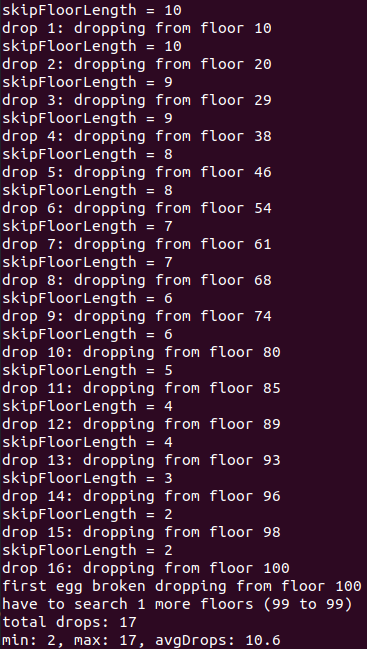

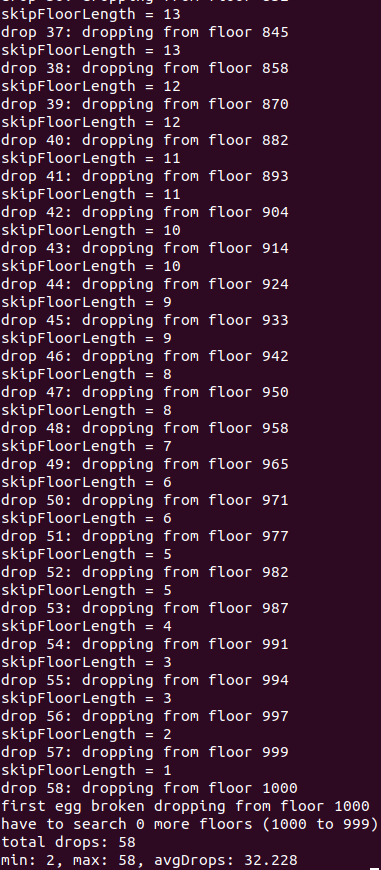

Anyway, one last thing for now. When coding this, I realized that if you're doing the optimal stride of sqrt(building height), and your first egg doesn't break... well, it's almost as if you're restarting the problem, but with a slightly shorter building! So, you shouldn't use the same stride that was calculated for the "original" building. That is, if building height = 100 and stride = 10, then if it survives the 10 and 20 floor drops, you still have two eggs and now it's kind of like you're doing the same problem with building height prime = 80, and ceil(sqrt(80)) = 9. So if you adjust this as you drop for each case, it should be better.

And it is! ...very incrementally.

Here it is for building height = 100:

and 1000:

(I just included more output so you can see it adjusting the stride.)

So it's better but not crazy better. At this point, there's a really good chance this method (best stride = sqrt of remaining floors) is the best strategy for this more general method (the "stride" method), though I still haven't actually proven it. But even if I did, that would only prove that it's the best strategy within the stride method. How do we know there isn't something better?

DP method

My much smarter friend Phil came up with a very clever way to get what has to theoretically be the best strategy, independent of any general strategy like the stride thing, using concepts from dynamic programming (DP). At the time I didn't understand it beyond the vaguest idea of "build up from the solutions to smaller subproblems", but since then I've learned a tiny bit about DP. So, I'm going to try it here in a few ways!

Until recently, my only experience with DP was a brief mention of building the Fibonacci sequence up from smaller terms we did in some CS class ages ago. I'll take the Fibonacci sequence as an example. It's frequently defined recursively as f(n) = f(n-1) + f(n-2), with the base case of f(1) = 1 and f(2) = 1. So you can calculate it that way. If you want f(100), now just calculate f(99) and f(98), and then to calculate each of those, calculate... etc. The problem is that, if you called this in the most naive way with a recursive function, it would explode into a huge number of terms, and more importantly, very redundant terms. For example (if you're trying to get f(100)), calculating f(99) needs f(98) and f(97), but you also need f(98) for f(100). So it's basically totally impractical for anything large.

An alternate way, the DP way, is to "build up to" the goal you want. So if we want f(100), we calculate f(3), which is easy since we have f(1) and f(2). Then f(4) from f(3) and f(2), etc. So you can see that it's way easier and involves storing way fewer numbers (basically just a single list of the ones you have calculated so far). Incidentally, this feels like a pretty contrived example, since I don't think any person who isn't already familiar with and eager to use recursion would define the Fibonacci sequence that way. I'm pretty sure I've usually heard people say "start with 1, 1, and then add the last two numbers to get the next number". So, peoples' intuitive default seems to be more like DP anyway.

But the point still stands: if we can break the problem into sub problems and then solve those easy subproblems first, the bigger problem will be a lot easier.

As I mentioned above, an important part of this problem is that, if there are 100 floors and you initially drop it at d=10 and it doesn't break, you now have to solve it for floors 11-100. However, since you still have two eggs and there's nothing at all special about these remaining floors, the remaining problem is completely identical to solving the initial problem, but with 90 floors instead of 100!

So here's my strategy. There's inherently a probabilistic nature to this that gets neatly taken care of with this formulation. I define a function v(f,d,e), which is the average number of egg drops that will be needed if there are f floors left to search, you drop the egg from floor d, and you have e eggs left, and for all following drops, you choose the optimal drop height. The last part is important because it mean that if you're calculating v(100,78,2), which is obviously a bad move (from what we've seen before, d=78 with 100 floors), we're calculating that quantity as if after that drop, all the following choices are optimal. When there are two eggs, I'll refer to the optimal value of v(f,d,2) as v(f) as shorthand.

This function can be divided up into two groups: 1 egg, and 2 eggs. 1 egg is simple, you just have to scan up from your highest non-break floor to the top. Therefore, v(f,*,1) = f-1, where I write * because it doesn't matter.

For two eggs, for a given drop, there are really two possibilities: it breaks or it doesn't. So we can define v(f,d,2) as the probability of it breaking times the drops needed if it breaks (v(d,*,1) because now you only have to scan up to floor d) plus the probability of it not breaking times the drops needed for solving the new subproblem with two eggs (v(f-d)).

If there are f floors left and you drop it from d, assuming the probability of it breaking from each floor is equal, then the chance of it breaking is (d/f) and the chance of it not breaking is ((f-d)/f).

So, using the above: v(f,d,2) = 1 + (d/f)*v(d,*,1) + ((f-d)/f)*v(f-d). The +1 is because you need to include this current drop for all the ones you consider.

And now we have a recursive relationship that we can use DP to build from! Remember, that v(f-d) is the number of drops using best play.

Lastly, how do you actually use this? It's assuming you can just plug in the value for the best play, but how do we get that? Let's just start.

So we start with v(1) and v(2). If you have one floor to search, I think we're basically defining the problem to say it's not at height 0, so you can assume that you don't have to search at all because you know it has to break on floor 1 (maybe this is wrong, but it shouldn't change the principal or the answers more than 1, I think). So v(1) = 0. For v(2), you can either do d=1 or d=2. If you do d=1, and it breaks, you're set. If it doesn't, you know it breaks on 2 anyway, so still good. If you do d=2, it has to break, but you still don't know whether it would have broken on d=1, so you haven't learned anything and have to try again.

So: v(2,1,2) =1 + (1/2)*0 + (1/2)*v(1) = 1. On the other hand, v(2,2,2) = 1 + (2/2)*1 + (0)*v(0) = 2. So we see that d=1 is optimal on average for f=2, so v(2) = 1.

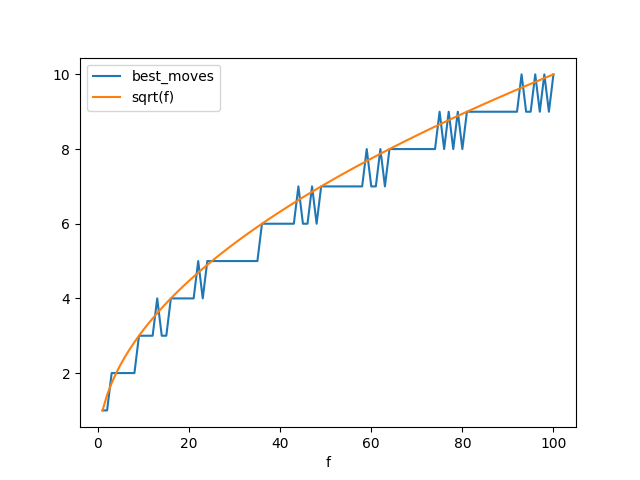

Now, you can do the same thing to get v(3), which will have to consider d={1,2,3} and evaluate each. So, at each step, we're taking the argmin to get the best d, and add it to the list.

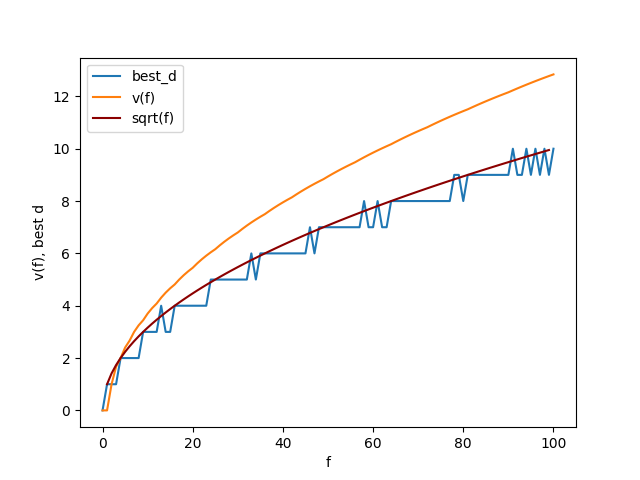

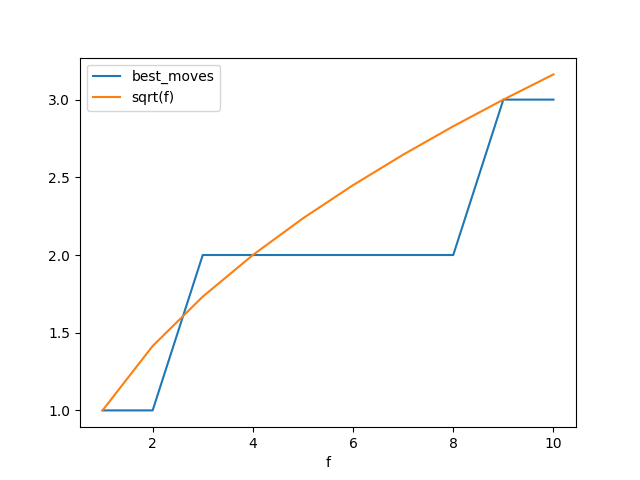

So how does it do? Pretty sweet!

You can see that the best d tracks sqrt(f) perfectly (with some weird wobbles?). v(100), which should be the average number of drops needed from 100, doing it perfectly, is actually 12.8. That's a little weird because if you look above, my brute force method for d = 10 gave an average of 10.9. I haven't looked into why this is yet, but I'm probably undercounting in one or overcounting in another (I'm guessing at one of the edge cases, like d=1 or d=100).

Here's the code for that:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from datetime import datetime

def v1egg(f):

return(f-1)

#This is for floors 0 and 1, the anchor cases.

v2egg = [0,0]

best_d = [0,1]

f_limit = 100

for f in range(2,f_limit+1):

vd = [1 + (d*1.0/f)*v1egg(d) + ((1.0*f-d)/f)*v2egg[f-d] for d in range(1,f+1)]

min_d = min(vd)

best_d_ind = np.argmin(vd)

best_d.append(best_d_ind + 1)

v2egg.append(min_d)

print('best for f = {}: avg={}, best move={}'.format(f_limit,v2egg[f_limit],best_d[f_limit]))

print('best d', best_d[:20])

plt.xlabel('f')

plt.ylabel('v(f), best d')

plt.plot(best_d,label='best_d')

plt.plot(v2egg,label='v(f)')

x = np.arange(1,f)

plt.plot(x,np.sqrt(x),label='sqrt(f)',color='darkred')

plt.legend()

date_string = datetime.now().strftime("%H-%M-%S")

plt.savefig('eggdrop_DP_{}floor_{}.png'.format(f_limit,date_string))

plt.show()

Markov Decision Process

So that worked pretty quick, but I recently learned a little about Markov Decision Processes (MDP) and wanted to use my new fancy knowledge! I realized that it could probably also be used to solve this, so I tried that. I don't think I can fully explain what MDPs are, but I'll just say a tiny bit that's relevant for what I did.

In a MDP, you have a set of states your system can be in. For this problem, a state is (f,e), where f is the number of floors left (i.e., floors you still need to search to find the break floor) and e is how many eggs left, plus one state I call the "solved" state. So if there are N floors, there are 2*N+1 states. You also have a set of actions that can take you from one state to another. Here, it's the set of floors you can drop to (plus the solved state), so there are N+1 actions. You also have a reward matrix, R_s,a, which is a reward you get if you take action a from state s. You also have a transition matrix, P_a,s,s', which is the probability, if you take action a in state s, that you actually get to state s'. So if the system is stochastic, and if you're in state s and take action a, you could end up in a few different states defined by P_a,s,s'. Because this matrix has an entry for every action and every pair of states, it can be pretty big. In our case, it will be (N+1)*(2*N+1)^2. You also have a state-value function, v(s), which gives you the value of being in a current state, so here is just N+1 long.

Lastly, you have your policy, p_s,a (usually denoted by pi but I'll use p here). This is generally the goal in MDP or maybe more generally reinforcement learning, because if you solve p, it tells you the optimal action to take in every state. For every state s, it has an array of weights for each action a, so is size (2*N+1)*(N+1). Eventually, these weights should settle (at least in this problem, but maybe always as long as P and R are not time dependent?) so that only one of them is nonzero. Until then, it will add its own stochastic-ness (like P_a,s,s') by trying different actions in the same state.

In this problem, pi and v will be changing, because you'll be solving for them. P and R will be static and known. P and R will essentially fully describe the system, but kind of indirectly and not in the most useful way. Therefore, we want to solve for v, which will describe the system in a more useful way (i.e., "it's good to be in this state, bad to be in that one"). We'll use this to solve for p, because we want to know what to actually do, also.

Okay, so how do we solve this?

It gets a little mathy at this point. Here's the idea, though. There's also a matrix, similar to v(s), called the action-value function, q_s,a. Similar to how v(s) is just the value of being in that state, q_s,a is the value of taking action a in state s. This is obviously going to contain R_s,a, but also has to include all the possible future rewards the system could get from other states and their rewards/actions.

So: q_s,a = R_s,a + gamma*sum_s'(P_a,s,s'*v(s')). So q is basically the reward for immediately taking that action, plus the value of every state it could immediately end up in times the chance it'll actually get in that state. The gamma variable is just how much you want to count future rewards. We want to completely in this problem, so we'll say gamma=1 and forget about it.

Okay, so that's q. On the other hand, the original v(s) can be calculated by, for each action a you can take from s, adding up the product of your policy for taking that action in this state, p_s,a, and the action-value for taking a in state s, q_s,a: v(s) = sum_a(p_s,a*q_s,a). So now we have v(s) as a function of q_s,a, and q_s,a as a function of v(s). This allows us to plug q in, and get a kind of recursive function of v:

v(s) = sum_a(p_s,a*sum_s'(P_a,s,s'*v(s')))

This is kind of funny at first glance, v(s) containing itself (partly). However, there's a theorem that says that if you update v with the equation above using the values it currently has, and the current values of p (as well as the static values of P and R), it has to approach the correct v. At each step, we also update p by, for each state, taking the argmax of the action-value q for all the actions it can take in that state. Basically, looking at the best choice it has in a state, based on our current v.

Oof, okay. To the actual problem. So the main task here is choosing P and R matrices that accurately describe the system. In these matrices, I've ordered the states such that index 0 is the solved state, [1,N] are the 1 egg states, and [N+1,2N+1] are the 2 egg states. For the actions, index 0 is going into the solved state, and [1,N] are dropping on that index's floor.

So it's a little confusing, because you have to incentivize the process in a strange way. For example, I only want states with one egg to be able to go to the solved state (which will mean they're scanning up from floor 1), so R_(f,1 egg state),(to solved state) will have reward -(f-1), but 2 egg states will have a huge negative reward (like -900). R_(solved, to solved) is zero, which is fine.

For ordinary 2 egg drops, the reward for every action to a state with the floor below its current floor will be -1 (takes one drop). I think we could actually also let the reward for going to states above our current state also be -1, and it would be disincentivized by it just being a longer path to the solved state, but to be sure, I also set the reward for those to be a large negative.

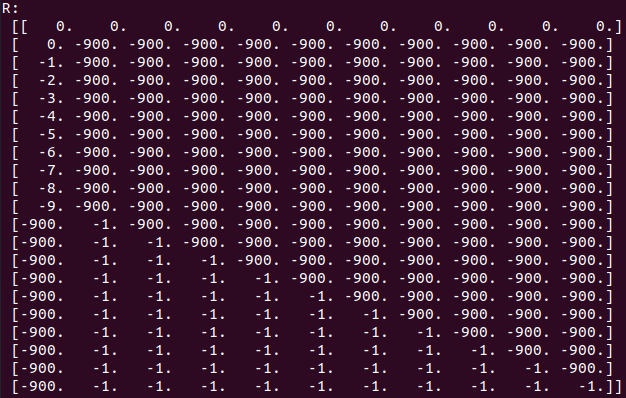

So at this point, for N=10 floors, here's what R_s,a looks like. The rows are for each s, the columns are for a.

You can see that the only "allowed" (i.e., not massively negative) actions are either the scan up for 1 egg states, or an ordinary drop for two egg states.

So that's for R. P_a,s,s' is basically three dimensional (or 2D and huge), so I can't really write it here. I'm not even sure I could have it in code as a matrix, because it would be of size N^3 (maybe for 100 would be okay). So I basically made it a function instead, which you call with the three arguments a,s,s'. Because it's kind of enforcing some rules, it is a trainwreck of if/else statements, but it works. The main idea is that most the P values will be 0 or 1, except for the "ordinary 2 egg drops", which will "branch" with probabilities d/f and 1-d/f (like above).

Anyway, once I've set up P and R, I just initialize p and v randomly, and I'm off to the races! For some iterations, I'll repeatedly calculate the new v, use that to update p, and then repeat. Here's the relevant code:

def policyEval(v,pi,R):

gamma = 1

v_next = np.zeros(v.shape)

for s in range(len(v_next)):

v_sum = sum( [ pi[s][a]*(R[s][a] + gamma*sum([Pmat(a,s,s2)*v[s2] for s2 in range(len(v))])) for a in range(pi.shape[1])] )

v_next[s] = v_sum

return(v_next)

def policyImprove(v,pi,R):

pi_new = np.zeros(pi.shape)

for s in range(len(v)):

q_list = [sum( [R[s][a]] + [Pmat(a,s,s2)*v[s2] for s2 in range(len(v))]) for a in range(pi.shape[1])]

best_a = np.argmax(q_list)

pi_new[s][best_a] = 1.0

return(pi_new)

v_log = np.array([v])

for i in range(20):

print(i)

v = policyEval(v,Pi_sa,R_sa)

v_log = np.concatenate((v_log,[v]))

Pi_sa = policyImprove(v,Pi_sa,R_sa)

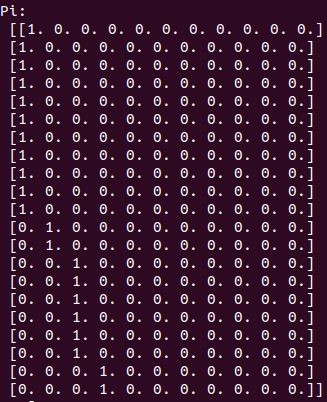

After this is done, we can look at p:

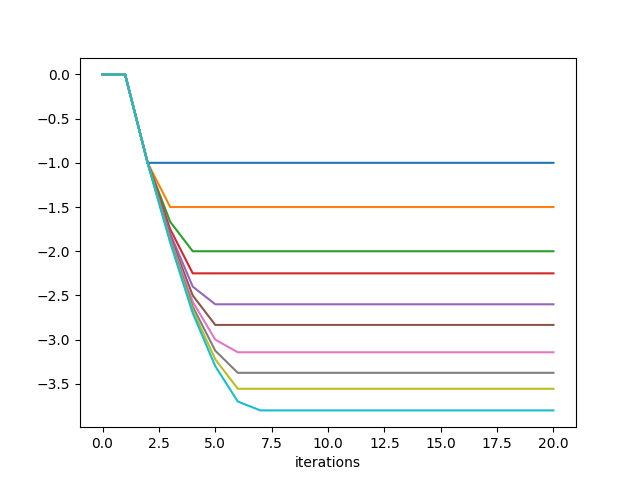

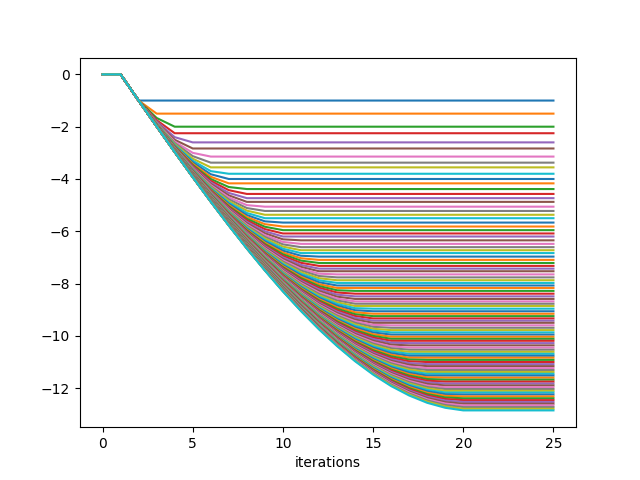

A little harder to read, but if you look at the bottom half of it, those are the probabilities for each action (column) in each state (row). We can plot the values of v(s) as it was improving:

And also the 2 egg state entries of p, for each row (if you look, there is just a single 1 in each row. So we're plotting the indices of those 1's here):

Pretty cool! You can see that for N=10, v plateaus at roughly iteration 8.

N=100:

v values:

argmax(p):

This actually takes a couple minutes to run. You can see that while N=10 needed 10 iterations, N=100 only needed about 20. Hmmmm.

The last value for v is actually -12.85, which is exactly what my DP method above found, so either they're both wrong in the same way, or I'm guessing my original brute force method wasn't counting the first or last drop or something.

Well, that's it for now. It's worth pointing out that this is only useful when you're already given R and P, so it's not really RL at this point, more just a method for solving some fully, but inconveniently described system. However, it should also be solvable if a P and R are defined, but not given to it, and it's allowed to sample many drops. Maybe I'll try that next time!