Genetic Algorithms are cool!

I was recently skimming through Russel and Norvig's AI: A Modern Approach and came to the section on Genetic Algorithms (GA). Briefly, they're a type of algorithm inspired by genetics and evolution, in which you have a problem you'd like to solve and some initial attempts at solutions to the problem, and you combine those solutions (and randomly alter them slightly) to hopefully produce better solutions. It's cool for several reasons, but one really cool one is that they're often used to "evolve" to an optimal solution in things like design of objects (see the antenna in the Wikipedia article). So, that's kind of doing evolution on objects rather than living things. Just take a look at the applications they're used for.

A lot of it makes more sense when you look at it in the context of evolution, because it's a pretty decent analogy. A GA "solution attempt" I mentioned above is called an "individual", like the individual of a species. It could be in many different formats (a string, a 2D array, etc), depending on the problem. You call the group of individuals you currently have the "population". For species in nature, the "problem" they're trying to solve is finding the best way to survive and pass on their genes, given the environment. For real evolution and genetics, the success of an individual is somewhat binary: does it pass on its genes, or not? (I guess you could actually also consider that there are grades of passing on your genes; i.e., it might be better to have 10 offspring than 1.) For GA, the success is measured by a "fitness function", which is a heuristic that you have to choose, depending on the problem.

For each generation, you have a population of different individuals. To continue the analogy, real species mate, and create offspring with combined/mixed genes. In GA we do something called "crossover", in which the attributes of two individuals are mixed to produce another individual. Similarly, we introduce "mutations" to this new individual, where we slightly change some attribute of them. This is actually very important (see evidence below!), because it allows new qualities to be introduced to the population, which you wouldn't necessarily get if you just mixed together the current population repeatedly (exactly analogous with real evolution).

So, that's the rough idea: you have a population, you have them "mate" in some aspect to produce new individuals, you mutate those new ones a little, and now apply your fitness function (i.e., how good is this individual?), and keep some subset of this new population. You could keep the whole population if you wanted to -- but the number would quickly grow so large that you'd basically just be doing the same thing as a brute force search over all possible individuals.

I was aware of GA already, but had never actually implemented one. The example they use in AIMA was the 8 Queens problem (8QP), which is a fun little puzzle. Embarrassingly, for a chess player, I had never actually solved it! So I thought I'd dip my toe into GA and do it, and also maybe characterize it a little.

So, let's set it up! An "individual" here is obviously going to be a board state (i.e., where all the queens are). Most naively, you might think that means a board state is an 8x8 2D array, with 0's for "no queen on this spot" vs 1 for "queen here". But, if you look at the 8QP for a second, you'll quickly see that they each have to be on a different row, and different column. Therefore, you can really specify a board by an 8-long array of integers, where each index/entry represents a row, and the value of that entry is the column number than queen is in. So it's automatically constraining them to be in different rows, and it makes the coding a lot simpler.

What's the fitness function (FF)? You want some way of deciding how good a board is. A pretty obvious one for this problem is the number of pairs of queens that are attacking each other, for a given board state. If you solve the problem, FF = 0. So for this problem, you want a lower FF.

Here, crossover is combining two boards. To do this, we just choose a row number, and then split the two parents at that index, and create two new boards by swapping the sides. It's probably more easily explained in the code:

def mate(self,board1,board2):

board1 = deepcopy(board1)

board2 = deepcopy(board2)

crossover = randint(1,board1.board_size-1)

temp = board1.board_state[:crossover]

board1.board_state[:crossover] = board2.board_state[:crossover]

board2.board_state[:crossover] = temp

return(board1,board2)

Then, we take each of those boards and mutate them:

def mutate(self):

row = randint(0,self.board_size-1)

col = randint(0,self.board_size-1)

self.board_state[row] = col

How do you actually mate them, though? This seems to me like possibly a really important aspect of this. What I was doing for the mating was a "grid mate" thing (see below), just the first thing I naively thought of. You take every non-redundant pair of the population, choose a crossover point, and make the two children. This will give you N*(N-1) children, but I also keep the "parents" in there as well. So if I had a pop size N = 5, then I'd get 5 + 5*(5-1) = 25 new ones to choose from, and I choose the best N of them to be the new population.

I kind of wanted to go step by step, and understand the effect of each thing I do. So, the first thing I tried was doing it with no mutations.

No mutations

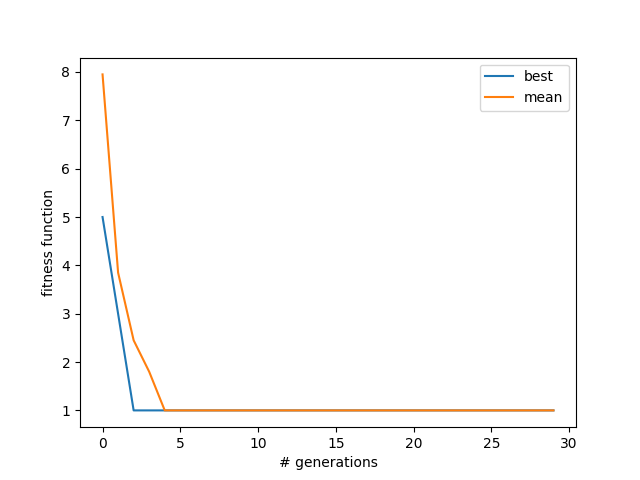

Here, Npop = 20, I run it for 30 generations, with no mutation. I've plotted the FF for the current best and mean of the population:

It quickly drops off to 1 -- but is probably stuck there because there are no mutations. So what the population can achieve is probably determined by the initial setup, since we're just switching bits by splicing. That is, if the solution needs a 3 in row 5, given your other available numbers in the population, you're out of luck if that number wasn't in that position for any of the initial population.

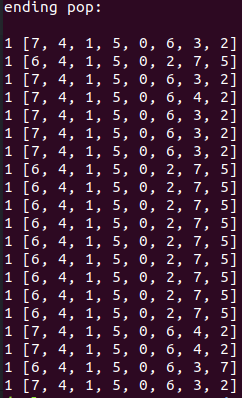

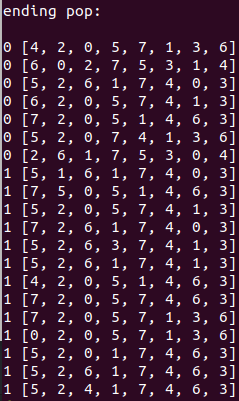

However, I was surprised that the mean was becoming the best value, so I took a look at the ending population:

(where the number in front is the FF and the list is the board state.)

Ahhhh. You can see that there are both a bunch of duplicates. I'm guessing that's because I'm keeping the parents: if the parent is a good option, it stays, but maybe its child also stays if it's decent. Then, the child turns back into the parent in some later generation, and now you have two parents. It seems like mutation (which I haven't included yet) might solve this, but I'm first gonna try just not including the parents.

Additionally, I might want to check for duplicates each time before selecting the top N to be the new population, because even with other fixes, I can't see how having dupes would help (well, depends how you're doing the mating I guess. Right now, the "grid" way I'm doing it, it would just be redundant. But I guess if you were doing it where it's like an actual population, where not every individual gets to mate, then you might want a very fit parent being represented multiple times? Maybe I'll cross that bridge when I get to it.).

So, not including the parents actually didn't help -- it seems like the population is able to "oscillate" between values and essentially still create duplicates. I'm actually going to add the parents back into the mix, so after it produces the children, it adds the parents to that list, and deletes the dupes from that list. Then, it sorts that whole thing by the FF and takes just the best N of them ("culling") to be the new population. Here's the relevant code that's doing that work:

def mateGrid(self):

new_boards = []

#Mating scheme

for i in range(self.popsize):

for j in range(i+1,self.popsize):

b1,b2 = self.mate(self.population[i],self.population[j])

new_boards.append(b1)

new_boards.append(b2)

old_and_new_boards = self.population + new_boards

self.population = self.deleteDupes(old_and_new_boards)

self.sortBoards()

self.sorted_population = self.sorted_population[:self.popsize]

self.population = [tuple[0] for tuple in self.sorted_population]

Getting rid of duplicates:

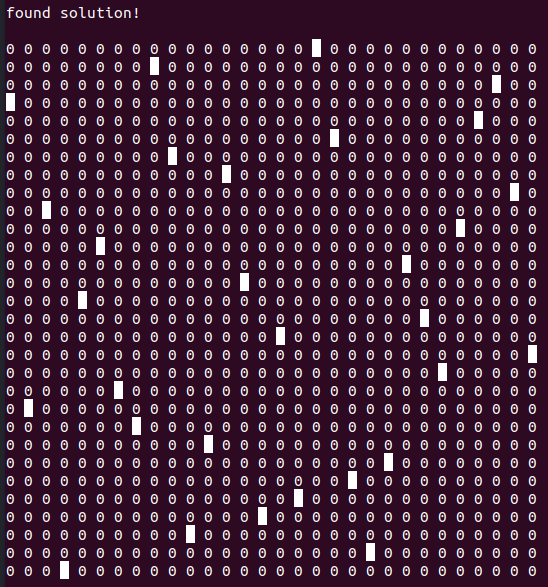

This is better behavior, in that the mean doesn't just automatically become the best (because it's full of duplicates) after a while. We're still limited by no mutations, though: a correct board configuration (which this sometimes finds anyway) is going to need a certain set of queens in a particular order; that is, it may need the first 3 entries to be something like [x, x+2, x+4, ...] (if you've ever looked at the solution, you can see that the queens are obviously "moved" by a knight's move, i.e., one over and two up). So, if the set of starting boards just never started with those numbers in those positions (across all of them), it'll never find a solution no matter how much you shuffle it.

Mutations

So let's introduce mutations!

Mutating all

Since I'm doing this without looking up much about it, I'm not sure where to actually introduce them, or how often. The AI book seems to show them mutating every time, after mating, no matter what. In my head, it would make sense to only mutate bad ones, or at least keep a copy of your best ones, since mutation is very likely to mess things up.

So what I'm going to do here is simply mutate everything after I combine the original population and the children, but before I delete the duplicates, by adding just a single line in the code above:

def mateGrid(self):

new_boards = []

#Mating scheme

for i in range(self.popsize):

for j in range(i+1,self.popsize):

b1,b2 = self.mate(self.population[i],self.population[j])

new_boards.append(b1)

new_boards.append(b2)

old_and_new_boards = self.population + new_boards

[board.mutate() for board in old_and_new_boards]

self.population = self.deleteDupes(old_and_new_boards)

self.sortBoards()

self.sorted_population = self.sorted_population[:self.popsize]

self.population = [tuple[0] for tuple in self.sorted_population]

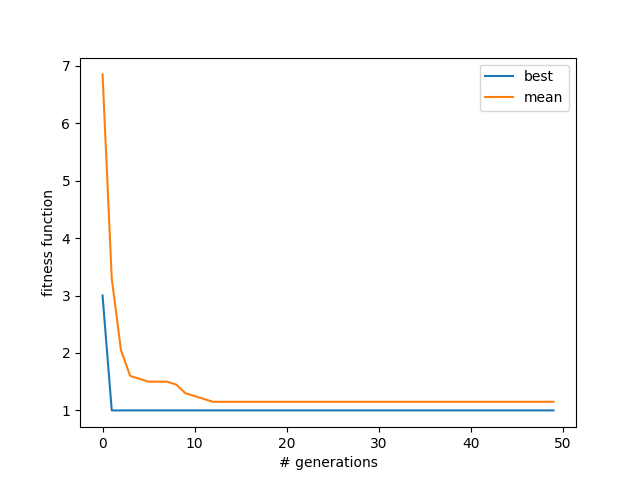

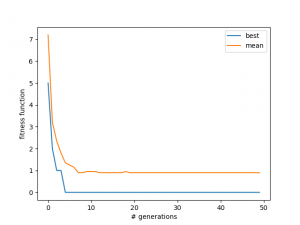

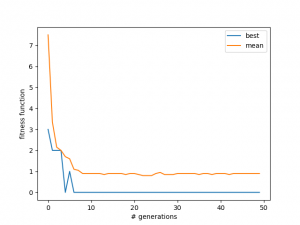

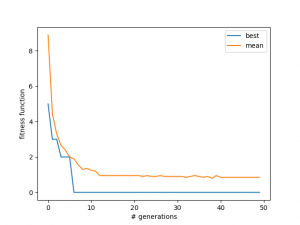

The results are pretty immediately striking. Here are three runs:

You can see in the 2nd one that it actually finds a solution, and then "un-finds" it. This is probably because it got mutated out. However, as time goes on this tends not to happen, because the population gets better as a whole, so if one solution is mutated away from being a solution, another almost-solution board will mutate into one, I think. You can also see that the average tends towards slightly less than 1 -- this is because in each case, only two solutions were found, and the others all have one attacking pair, so the mean is 18/20 in this case.

Mutating all, but keeping originals too

Some little quirk I might try is to add the original population back in again, right after the others have been mutated, before I delete dupes:

old_and_new_boards = deepcopy(self.population) + new_boards [board.mutate() for board in old_and_new_boards] self.population = self.deleteDupes(old_and_new_boards + self.population)

The deepcopy thing is an annoying little bug I almost missed! If you don't deepcopy self.population, it will mutate those and you won't be adding the old ones back (which we want to).

Anyway, adding this has pretty great results. With how it was before (not keeping the parents), the best ones got mutated away. This meant that the mean would sometimes go up a little, and you would see small drifts away from the solutions. That's not bad (if your goal is just to find a single solution), but it meant that it was only ever finding 2 solutions maximum (just for this set size, and my observations, not saying it has to be so).

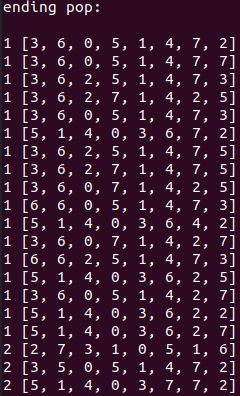

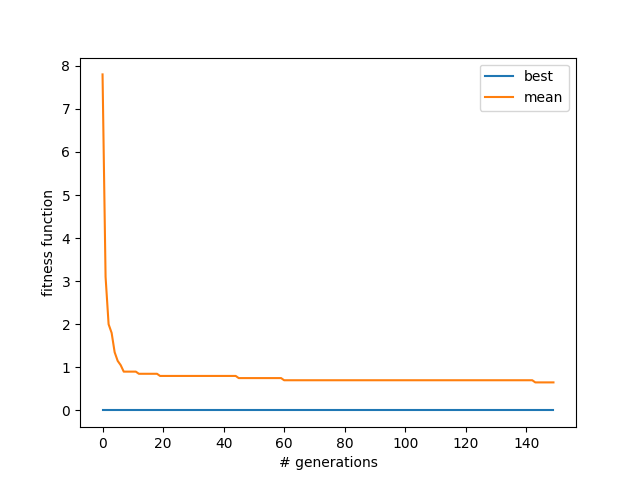

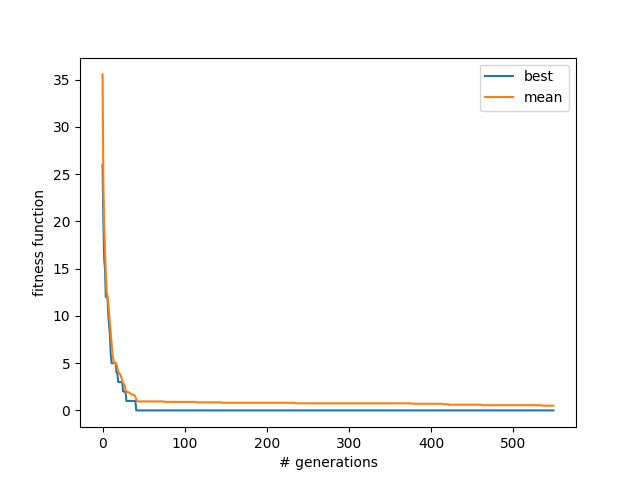

However, including the parents means that it will never drift from a solution (because it's keeping the best ones), and therefore the mean won't go up, because at worst it will just choose the ones from the last generation. Additionally, it's finding way more solutions! Usually 3-6:

Pretty cool. I guess not keeping the parents meant that solutions were always kind of ephemeral, so it could never accumulate many. You can also see that it's actually finding solutions way later than the original one, which tended to find any solutions pretty quick and then settle down. (It seems like the 'best' line there was 0 the whole time, so maybe it got lucky and started with a solution this time?)

What's also pretty cool you can notice here is what Russell and Norvig call a "schema", that is, a chunk of a solution. For example, above you can see that 2,0 as the 2nd and 3rd digits, or 1,3,6 as the last three digits, appears in several solutions. This is cool because it's kind of the algorithm naturally finding structure in the solution, and crossover allows the structures to combine such that they don't get destroyed (which would happen if you just mixed two boards randomly by index rather than choosing a crossover point).

Scaling it up

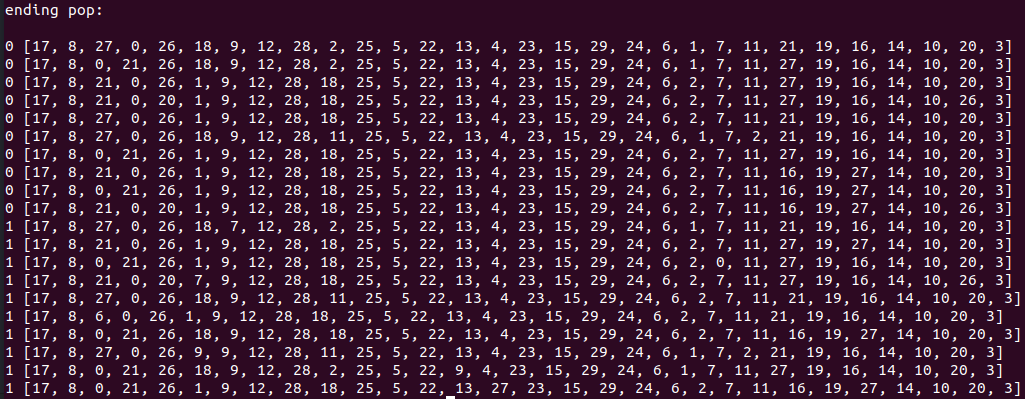

Of course, the 8QP might just be too easy. It's really one version of the more general N Queens problem. Let's try the 30 queens problem!

It still runs pretty damn fast, and finds solutions after about 40 generations. Also interestingly, it's still finding new ones after 500 generations (look for the little dips in the mean line near ~540).

Anyway, that's all for now. I'll probably do a part 2, because there are a bunch of things I want to explore:

- Make the Population more general? That is, make it so you can create an "individual" class with a mate() function and it will solve it the same way.

- I want to label old/new ones after a mutation, so we can see the average lifetime of given individuals.

- Double mutations! The sets of solutions this finds are only clearly centered around one or a couple minima. This is probably because it would take several steps/mutations to get to those very different ones. However, if you allow double or triple mutations (i.e., changing several things at once), you could possibly "hop out" of these specific minima.

- This seems similar to simulated annealing to me. It seems like I could add something like the Metropolis Algorithm/etc, where I sometimes accept worse individuals into the population, with some small percent. Similarly, it feels like the amount of mutating you do in a mating step is analogous to the temperature in the Metropolis Algorithm.

- How much worse is it if you do a random mixing of some proportion of the two parents, as opposed to crossover?

- How much harder is it to solve if you don't do the constraint we did of making it an 8-long array?

- Could we quantify the schemas we see in solutions?

- Cooler applications!